Dean Worcester’s Pro-Imperialist Message

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States acquired the territories of Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines from Spain, as stipulated in the Treaty of Paris following the Spanish-American War. Among the US government, scholars, elites, and the public, a question arose: what should the United States do with the newly-acquired Philippines?

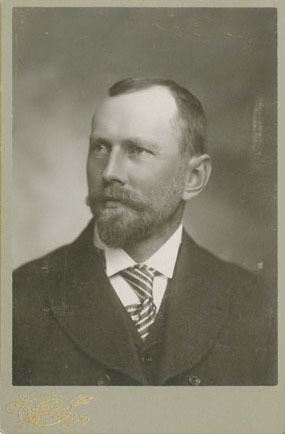

One influential contributor to the debate was Dean Conant Worcester, notable not only for his strong ties to the University of Michigan but also for his extensive trips and first-hand experience in the Philippines. Worcester attended the U-M from 1884 to 1889, during which he was a part of Joseph Beal Steere’s expedition to the Philippines. He graduated with a degree in zoology and later worked as an Assistant Professor at UM. Because of his involvement with the Philippine expedition, Worcester was considered to be among the most knowledgeable about the country, and his works and speeches helped shape the perception of the territory for the general American public. Thanks to his status as a Michigan alumnus and donations from his family, the Bentley Historical Library holds an extensive collection related to Worcester, his notes, and his published work.[1]

Dean Worcester used his prominence and status to promote a pro-imperialist message. On November 15, 1899, he gave a speech to the Hamilton Club at Central Music Hall in Chicago.[2] Though only recently established, the Hamilton Club was aleady well-known as a Republican party social club and meeting place.[3] Members congregated to discuss political topics in addition to enjoying the amenities that the club had to offer. As a political meeting ground, the Hamilton Club became influential in elections and political issues, especially when the Republican National Convention was held in Chicago. When Worcester gave his speech in November of 1899, the national presidential elections were less than a year away. He knew that the subject of imperialism in the Philippines and his thoughts on the matter would appeal to the crowd of Republicans.

Worcester’s speech to the Hamilton Club focused on discrediting the legitimacy of the Republic of the Philippines (declared after the Philippines war against Spain, in 1899), emphasizing the positive influence of American leaders, and diminishing the fact of hostility between Filipinos and Americans. His speech took place in the context of an ongoing, brutal war between the US and the Philippine revolutionaries throughout the archipelago.

First, Worcester claimed that Emilio Aguinaldo, the first president of the Republic of the Philippines, was not promised independence from Admiral Dewey, the leader of the American forces in the Philippines. Worcester cited letters that Aguinaldo wrote to US President William Mckinley that failed to mention any American promise of Philippine independence. According to Worcester, Aguinaldo insisted that no American promised to grant the Philippines its independence. Worcester attempted to set the record strait against characterizations of American dishonesty.[4]

Another of Worcester’s arguments, especially in response to anti-imperialist criticism, was that the Philippines was worse off under Spanish rule and would have continued on a similar path if Aguinaldo and other Tagalog leaders were in power.[5] Worcester pointed out that after the Philippine Revolution in 1897, Aguinaldo accepted a large sum of money and amnesty from the Spanish government and in exchange the revolutionary government was exiled to Hong Kong. Aguinaldo then put this sum of money in his personal bank account. Worcester contrasted Aguinaldo’s selfish and dishonest actions against those of a “legitimate” government: the United States. In painting Aguinaldo as corrupt, Worcester sought to demonstrate that Filipino leaders only had their own interests in mind and therefore lacked the capacity to govern their own people.

At the same time, Worcester attempted to prove that the Filipinos were allies of the Americans before the capture of Manila. He argued, for example, that the American Army did infinitely more than Aguinaldo’s army in driving out and destroying Spanish power, and that the Americans were just trying to help the Filipinos achieve sovereignty.[6] Worcester’s claim of alliance was tenuous at best, as there was never any true cooperation between American and Filipino forces. Worcester then contradicted himself, later mentioning that the situation in the Philippines grew worse as so-called Filipino “insurgents” became more hostile towards Americans after the fall of Manila.[7] An instance of this hostility came when an American sentry killed a Filipino, prompting retaliation, which resulted in more Filipinos who died.

The Americans never intended to declare war, according to Worcester. The Philippine-American War was just the unfortunate result of misunderstanding America's good intention to support Filipinos in their eventual self-governance. His message repeatedly laid blame for the conflict between Filipinos and Americans at the Filipinos’ feet. To a Republican audience, this speech may have been well-received. Worcester packaged US imperialism in ways that erased American violence, exploitation, and arrogance while aggrandizing America’s civilizing mission and sense of self-importance. For Americans who believed Worcester’s claims, US imperialism in the Philippines was an extension of American humanitarianism and good will.

Citations

[1] Dean C. Worcester Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Dean C. Worcester, “Some Aspects of the Philippine Question,” Hamilton Club of Chicago Serial Publications; No. 13. The Library and publication committee, 1900. Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor MI.

[3] Hamilton Club of Chicago (Chicago 1899).

[4] Dean C. Worcester, “Some Aspects of the Philippine Question.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.