Content Warning: This page describes racial violence and racist language

Identifying an Enemy

The Filipino Revolutionary in The Alumnus

Emilio Aguinaldo, a Filipino Revolutionary and the nation's first president, established the Philippine Republic in 1899, following the anti-colonial revolution against Spain. Things were looking up for the Filipinos, except for the arrival of the Americans in 1898, which would change the future of the newfound republic. Just as the Philippine Revolution began to see success, American imperialists declared all Filipino revolutionaries "insurrectos" (insurgents) in order to undermine their efforts. The depiction of Filipino revolutionaries as an enemy proliferated within US media, including in newspaper and magazine publications in the state of Michigan. For American audiences with little prior exposure to Filipinos or Philippine culture, these publications played a powerful role in shaping US opinion on the so-called Philippine insurrection.

In the UM Alumni Association's magazine, The Alumnus, Filipino troops were described as "insurgents" who willfully rebelled against peaceful, benevolent US officials. According to one article about Frank S. Burns, an alum who served in the Philippines from 1890-1893, the US military attempted to "conduct negotiations with Aguinaldo and other insurgent leaders."[1] The article treated Burns's experience as a negotiation with criminals rather than a legitimate exchange between military officials. The Alumnus also reprinted a letter sent from General Francis Vinton Greene in the Philippines to Bourns’ father in which he praised Bourns for his ability to translate documents to and from Spanish.[2] He stated that Bourns conducted interviews “with Spanish officials or insurgents [emphasis added].”[3] The casual usage of the term in this sentence reveals how commonplace it was to assume that Filipinos were not legitimate soldiers. In these pieces, Filipinos were never described as “officials,” “soldiers” or other labels used to describe military groups.[4]

As historian Paul Kramer argues, the US government's characterization of the Filipino Revolutionaries as “a set of fragmented and warring ‘tribes’ that were ‘incapable’ of nationality” and self-government" benefitted US imperial interests.[5] With a similar rhetoric, articles in The Alumnus erased the Filipinos' long struggle for freedom in order to persuade Americans of the morality of US imperialism. According to UM law professor Bradley M. Thompson, the US possessed a “moral duty” to civilize and elevate the Filipinos so that they might one day be ready for self-government.[6] With close ties to the colonial project, the University of Michigan community produced the image of chaos, disorder, and ruthless violence through the narrative of the Filipino-as-insurgent in order to justify American intervention. In the process, the magazine downplayed the harm caused by the US government including the US military's destruction of homes and property, violence against civillians, and psychological warfare.[7]

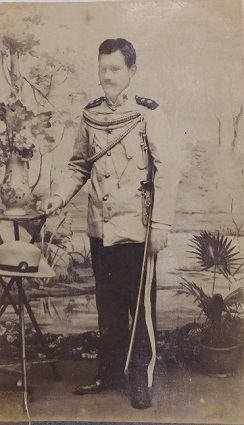

We see the same narrative of Filipino-as-insurgent in many of the Philippine collections at the Bentley Historical Library. The papers of Owen Tomlinson, an officer in the Philippine Constabulary, contain photographs of Filipino leaders taken by US soldiers during the war. Figure 1 shows a Filipino captain standing in uniform in front of trees and plants. The caption written on the back of the image reads, “Insurrecto Captain Captured in Tarlac Province.” Although there is not enough information from the caption and image to know who this man was, it does indicate something about the perspective of US soldiers. The photo raises several questions: Why did US soldiers take this photo? What message did they hope to create through photographs?

In Figure 1, the Filipino captain is notably standing and looking away from the camera. His clothing does not appear dirty or torn as one might imagine it would in a war scene. His hat is delicately placed on a small stand in front of him. The background of the image—flowers, plants, a vase—is pleasant and peaceful. The captain is alone and positioned at the center of the image. Meanwhile, the caption describes him as “captured.” He is under the possession of the US military (captured by force) and recorded and documented by the camera (captured by photographic technology). One way to interpret these creative decisions is to consider what they tell us about the US military’s narrative of power and control. Photography does not document objectively, but rather conveys specific messages produced by the photographer. The image conveys US military domination over the Filipino subject yet elides the violence of the war. The posing of the Filipino captain as clean and untouched by battle suggests humane treatment, which conflicts with archival accounts of torture at the hands of the US military. The peaceful background suggests that US forces were moving closer to winning the war and pacifying the country.

Figure 2 also comes from the papers of Owen Tomlinson. It was taken by Frank T. Corriston, a member of the Minnesota Infantry Regiment. In the image, we see a group of Filipino soldiers whom the US held as prisoners in Manila. Similar to Figure 1, the caption of this photo describes the group of men pictured as insurgents. Yet, in contrast to Figure 1, the Filipinos pictured here are posed next to a group of American soldiers. Three tall white men stand in juxtaposition to indigenous Filipinos in loincloths, also known as bahag, and hats or bandanas. The contrast in height, skin color, and dress emphasized a difference between “civilized” combatants and “uncivilized” “warring tribes.” According to imperial logic, how could a group of so-called primitive men be respected as soldiers?

In Figure 2, the contrasting soldiers are placed at the center of a town scene. Crowds of people wearing white walk about apparently unaware of the camera. The image conveys a sense of order and control among the civilian population, providing what may have been a surprising vision for the spectator expecting to see a war zone. Through this photo, the US military could claim that Tarlac province was overcoming the problem of insurgency, and that the people were almost ready for the project of US colonial tutelage.

Consequences of the “insurgent” in the Archive

The photographs from the Tomlinson collection, as well as the accounts from The Alumnus, reveal one of the pitfalls of archival research. Archives amplify some voices and silence others if the records they contain only present one perspective. In the case of the Bentley Historical Library, the majority of the archival collection related to the Philippine-American War was produced by individuals who supported the war and the American colonial project.

One consequence of archival silencing is that the perspectives represented become authoritative. The histories of the Philippine-American War produced by American historians of the early twentieth century exemplify this problem. Through the production of historical narratives, supposedly based on objective evidence, American historians of this generation perpetuated the insurgent narrative decades after the war.

While recognizing this problem, we sought to find sources buried deep within the archive that might provide a glimpse of an alternative narrative. This comes from the collection of Simeon Ola, a Filipino Brigadier General who led troops in the province of Albay. He tells us a story of Filipinos as heroes and the war as a revolution. Ola’s papers contain a 1938 application he submitted to the Philippine government requesting a pension for his military service during the Philippine-American War.[8] Accompanying the application was a letter to the President of the Philippines, Manuel L. Quezon, in which Ola wrote that he wanted “to obtain the benefits in the form of a pension which under the existing laws other comrades enjoy."[9] The fact that veterans of the Philippine-American war were eligible to receive pensions for their military service suggests that the Philippine government recognized Filipino troops as soldiers rather than rebels. Although they are brief and few, Ola’s papers are an invaluable collection because they provide a different perspective on the "enemy" of the Philippine-American War.

Citations

[1] “University Men at the Philippines,” Michigan Alumnus 5, no. 6 (March 1899): 247.

[2] Dean Worcester, "Michigan in the War: An Addendum," Michigan Alumnus 5, no. 4 (January 1899): 143.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See also, Theodore Vlademiroff, "A Letter From the Philippines," Michigan Alumnus 6, no. 5 (January 1900): 180. An engineer aboard the USS Helena named Theodore Vlademiroff described a battle near the town of Parañaque where, he claimed, the Helena “wrought heavy losses upon the retreating insurgents."

[5] Paul A. Kramer, Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 90.

[6] “Defends Imperialism,” Michigan Daily (Ann Arbor, MI), Mar. 2, 1899, The Michigan Daily Digital Archives, Bentley Historical Library, accessed 5/27/2019.

[7] For more on the US military's atrocities during the Philippine-American war, see Reynaldo C. Ileto, “The Philippine-American War: Friendship and Forgetting,” in Vestiges of War: The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream, 1899-1999, ed. Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2002).

[8] Petition to the Philippine Government to Receive a Pension for his Military Service during the Philippine Revolution, Sep. 7, 1928, translated into English by Norman Owen, Simeon Ola Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Letter from Brigadier General Simeon Ola to President Manuel L. Quezon, May 17, 1938, translated into English by Norman Owens, Simeon Ola Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.