Content Warning: This post discusses policing, criminalization, and sexual violence, and describes gruesome acts of violence in detail.

Law and Order in the World's First Surveillance State

In Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State, Alfred McCoy argues that the Philippines was the first “surveillance state” in the world.[1] New ways of gathering information and data about others revolutionized colonial rule, modernizing the Manila police, creating the paramilitary Philippine Constabulary, and developing photographic identification to monitor the everyday lives of Filipinos.[2] The Philippines became a laboratory for the US government, which tested its new information technologies without limitations or the need to abide by the US Constitution's protection of civil liberties.

After the Spanish-American war, the Philippine-American War was the second US war to be fought outside of the Western-Hemisphere. It came after decades of improvements in US military intelligence [3]. The Philippine-American War was also one of the first wars to be heavily documented through photographs due to new technologies such as the Kodak camera. Companies such as Edison Manufacturing filmed “actual war footage on the battlefields and later reenacted battle scenes from the war” [4]. The significance of such technology is that it rendered the war in the Philippines an object of consumption by American and colonial audiences. By heavily documenting and re-creating battlefield footage, the war was brought home to millions of Americans at the turn of the 20th century.

What was the impact of documenting, creating, re-creating, and archiving the Filipino? What did it mean to document violence and the torture of Filipinos, and place these images in juxtaposition with images of peace and order? How did such images contribute to developing a surveillance state? Through archival research and critical reading lenses provided through the work of historians like Alfred McCoy and Paul Kramer, we can begin to see how policing through photography and film became another means for the US to exert unlimited colonial power.

The Philippine-American War photograph collection housed at the Bentley Historical Library in Ann Arbor, Michigan, contains multiple narratives of the war. The very first photograph found in the collection’s small white box is of dead Filipinos, presumably revolutionaries who continued their fight for independence when the Americans took over from Spain (Figure 1).[5] By stark comparison, another photo in the collection depicts American families having a picnic in nature (Figure 2).[6] Figure 1 includes no captions, and there are no details surrounding the soldiers’ deaths or the location of the battlefield in which they were killed. The soldiers remain nameless, and the photograph can only be identified as “683,” the number that is written on the bottom right corner of the photo. Figure 2 depicts American families having a picnic by what seems to be a body of water. In the photo, there are two Filipino men dressed in white, though it is unclear who they are or what their relationship is with the Americans.

In the absence of further documentation, the critical historian has to probe deeper into the logics behind these photographs, given their greater context of circulation. Photographs of dead soldiers devoid of any individual identification (such as names) may serve to project both triumph and terror: triumph for the Americans at home possibly consuming these images, and terror for Filipinos who might take these images as warnings of what happens when one dares resist the colonial state. Photographs of happy white colonials and their Filipino companions, meanwhile, might be taken by Americans curious about the Philippines as signs of convivial coexistence, and as a suggestion for Filipinos that with submission, comes peace. Surveillance and policing in this case is no less powerful for being indirect: indeed, the ultimate goal of many technologies of surveillance is to train people to police themselves.

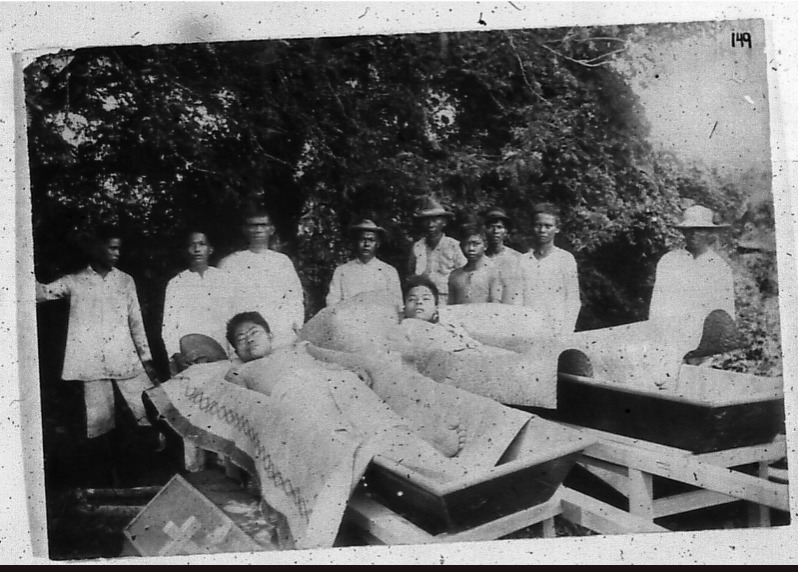

The contrast illustrated by the photos of smiling Americans and dead Filipino revolutionary fighters could be found in other archival material as well. In the papers belonging to Harry Hill Bandholtz, a professor from what is known today as Michigan State University, similar juxtapositions appear.[6] Pictures of Filipino families are mixed with photographs documenting the hangings of Filipino men who were found guilty by American colonial courts. “Law and order” policing could be as brutal as the Philippine-American war, as judicial systems made to look like the American system often operated in imperialist ways.

There were many reasons as to why thousands of Filipino men and women were tried and found guilty in the US-established courts in the Philippines under US law, and the creation of the American judicial system in the Philippines does not lay far outside of Michigan’s sphere of influence. George A. Malcolm, a 1906 graduate from the University of Michigan’s Law School established the law school of the University of the Philippines and became its Dean in 1912.[8] Five years after becoming Dean, Malcolm was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines. In this role, Malcolm effectively institutionalized the imperial ideologies of other “Michigan Men” like Dean Worcester, James LeRoy, and Owen Tomlinson.[9]

While serving as the Dean of the Law School, Malcolm was tasked with evaluating the capability of Filipinos to “self-govern.”[10] In his letter to President Wilson, he explained that he would give up his position as Dean should a Filipino suited for his position be made available.[11] In the library lay numerous cases that had reached the Philippines Supreme Court that Malcolm legally weighed in on. Many of the cases were concerned with heroin and cocaine use or trading.[12] Filipino men received a harsh punishment for owning, using, or even passing by property that was associated with opium. Although Malcolm eagerly prosecuted Filipinos who were caught in possession of opium, US laws in the Philippines, and even nationally, were at first not opposed to heroin. As historians have noted, a combination of factors led to the prohibition of opium, among which were protestations by missionaries, who were worried about the effects of consumption in their mission fields and on potential converts. Likewise, in the Philippines, missionaries also played a role, generating knowledge about Filipinos and regulating their day to day lives. There was an ostensibly moral element to policing that served to justify the harsh punishment.

Through the creation of a US-based judicial system in the Philippines left unchecked, the courts used their own discretion to determine the right punishment for their so-called “little brown brothers.” While opium use was sometimes met with decades of jail time, rape and murder were given life sentences or death penalties. The latter fate would be the case of Leoncio Tabordan.[13] Under the US-established “Headquarters Department of Southern Luzon,” Tabordan was found guilty of torturing and killing another Filipino by the name of Tomas Ragudo.[14] Bandholtz documented American soldiers going to Tabordan’s home to take him, and a paper after his hanging documented his death.[15] It is unclear if the soldiers at Tabordan’s door were arresting him or taking him to the place of his execution.[16]

A 1902 US Senate document entitled Affairs in the Philippine Islands: Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines of the United States Senate is packed with hundreds of other court orders in which the US found these men guilty under its own law.[17] Indeed, the imperial archive is replete with materials depicting colonial law and order, often visually and sometimes graphically. Within Tomlinson’s collected images there are also photographs of Filipino men caught headhunting held in handcuffs. In other cases, Bandholtz captured pictures of dead Filipino bodies after they were hanged.

Like the images from the Philippine-American war, the photographs documenting the punishment of so-called criminals also projected both triumph and terror towards the goal of surveillance. The documentation of state violence such as executions might represent justice and order for white colonials uncertain of the stability of the colony. The moral component of policing helped to ensure that punishment was logical and necessary, even if criminals were not fairly tried. And again, these violent images reminded the public of the power of the colonial state even in times of peace. US colonialism in the Philippines included creating a judicial system in which Filipinos could be put on trial and found guilty without the ability to contest their rulings. As the archive reveals, this kind of state violence was made possible through the power of surveillance. The paramilitary Philippine Constabulary and other police forces throughout the colony not only engaged in acts of violence such as beatings, torture, and rape, but they documented their actions in ways that legitimated the use of force and criminalized the Filipino population. Policing the Philippines--or creating the perception of “law and order”--became an even more powerful strategy for controlling the colonized when combined with methods of surveillance.

Historians such as Alfred McCoy have argued that the American colonial Philippines was a laboratory for the uneven administration of law and punishment--an issue that continues to shape the culture of policing in the United States and US forces abroad. Similar practices were uncovered in the US occupation of Iraq, for example, through the case of Abu Ghraib. Iraqi men were found guilty and tortured in Abu Ghraib without a trial, and only under the suspicion of being terrorists. Moreover, the photos at the scene at Abu Ghraib, which sexualized Muslim victims of torture, mimicked the kind of documentation of violence that we have seen in the Philippines. The photos at Abu Ghraib served as evidence of American power over subjects perceived to be violent, and therefore culpable and deserving of punishment. The circulation of the photos among the American public also turned white perpetrators into the victims, erasing the responsibility of US military personnel in committing the crimes. By closely examining the colonial Philippines, we might be able to draw even more connections to US military and colonial contexts both in the US and around the world.

Citations

[1] Alfred W. McCoy, "Policing the imperial periphery: Philippine pacification and the rise of the US national security state" in Alfred W McCoy and Francisco Antonio Scarano, Colonial Crucible: Empire in the Making of the Modern American State (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009).

[2] Ibid. According to Alfred McCoy, “The American regime in Manila drew together theories and technologies that had been building for decades in the United States into a colonial praxis of coercion and information-fostering innovations, data management, and shoe-leather surveillance whose confluence created a modern surveillance state,” 108.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Nerissa Balce, Body Parts of Empire: Visual Abjection, Filipino Images, and the American Archive (University of Michigan Press 24, 2016).

[5] Philippine American War photograph collection, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Harry H. Bandholtz Papers Microform 1890-1937, 1899-1925, Roll 11., Harry H. Bandholtz Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[8] George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] George A. Malcolm papers 1896-1965, Decisions 1917-1918, Box 5., George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[10] Ibid.

[11] George A. Malcolm papers 1896-1965, Opinions 1913, Box 5., George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[12] George A. Malcolm papers 1896-1965, Decisions 1917-1918, Box 5., George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[13] US Senate, "Affairs in the Philippine Islands: Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines of the United States Senate." Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (1902).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Harry H. Bandholtz Papers Microform 1890-1937, 1899-1925, Roll 11., Harry H. Bandholtz Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[16] Senate, US "Affairs in the Philippine Islands: Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines of the United States Senate." Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (1902). This document describes the torture that Tabordan and other men allegedly committed. However, It is unknown how these details were obtained, thereby calling into question the legitimacy of the accusations against the Filipinos.

[17] Ibid.