The Pensionados and the Image of the Filipino ‘Primitive’

At the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, the US Philippine Exposition featured a living display of the Igorots, an indigenous group of the Philippines.[1] The exposition, alongside the publications, speeches, and photography of American imperialists in the Philippines, produced the image of the Filipino as a timeless “primitive.” Despite the diversity within Philippine cultures, this image dominated the American understanding of the Filipino. When pensionados, government-sponsored Filipino students, migrated to the US to study in American universities, they attempted to challenge this image. Within the United States, the pensionados were some of the most vocal critics of the depiction of “uncivilized” Filipinos.

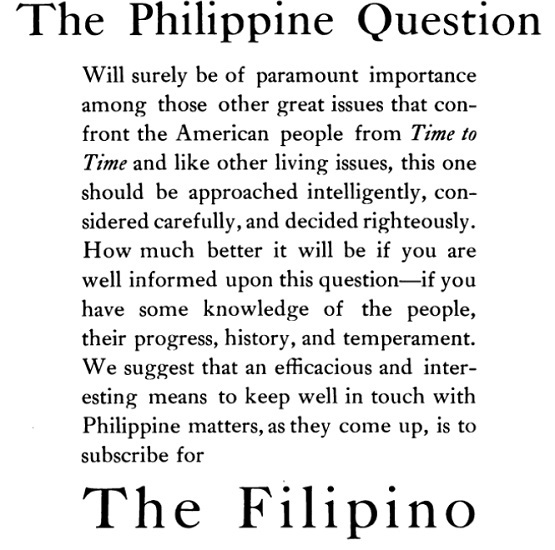

Pensionados studied at universities all across the US, including the University of Michigan, published a quarterly magazine in Washington DC called The Filipino to bring their voices together.[2] They intended the magazine to educate Americans in general about the Philippines and the Filipino people. An advertisement printed at the end of each issue (see Figure 1) promised that the question of Philippine independence would “surely be of paramount importance” for Americans in the future.[3] It then addressed Americans directly, saying “how much better it will be if you are well informed upon this question-if you have some knowledge of the people, their progress, history, and temperament.” Finally, the advertisement told Americans readers that if they wanted an “efficacious and interesting means to keep well in touch with Philippine matters” they should subscribe to The Filipino. This advertisement implied that Americans were not well informed, and that The Filipino would be a vehicle for the pensionados to represent Filipino culture to Americans.

In one editorial, published in Spanish, The Filipino directly criticized the American depiction of the Filipino. It stated that imperialists circulated unrealistic reports and photographs, such as those shown at the St. Louis World’s Fair, to mislead the American public.[4] This editorial, among many others, used multilingualism (in English and Spanish) and the education that pensionados received in the US, to persuade their audience that they were civilized and intelligent. The pensionados wanted the US public to know that they represented an elite class of Filipinos who did not fit the depictions that most Americans were familiar with.

The Filipino did not claim that the imperialist conception of uncivilization was entirely false, but that Americans had misapplied it to the majority of Filipinos. Pensionados came from elite families and had been raised as Catholics under the Spanish system that divided the population between Christians and non-Christians. They tended to agree with the viewpoint that the Igorot people—the indigenous group featured at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904—were uncivilized. However, they challenged the idea that Filipinos in general were uncivilized. One author lamented the exhibition of “Igorot Villages,” popularized in the midwest by Americans like Richard Schneidewind, noting, “it seems as though the Filipino people have before them a long lifework in attempting to counteract the impressions spread broadcast throughout America by those who so thoughtlessly exhibit savages belonging to our wild, uncivilized tribes in the islands.”[5] In another article, a pensionado wrote that the population of the Philippines could be “roughly divided into three classes—the aboriginal savages, the Mohammedan Malays (called Moros), and the civilized or Christian Filipinos.”[6] According to the author, the last group comprised “the real Filipinos, who politically and socially represent the Philippines Islands.” He also insisted that before the Spanish arrived in the Philippines, “nearly all the sources of modern civilization were present” in the Philippines among the Malays, “the ancestors of most of the Filipinos.” The pensionados argued that non-Christian natives were uncivilized savages, not the hispanized, Christian, who they believed were the “true” Filipino.

Instead of contextualizing or defending the cultural practices of non-Christian tribes, the pensionados argued that these practices did not represent the majority of the people in the Philippines because only a small percentage of people in the Philippines were non-Christian. They pointed out that there were only 650,000 non-Christians out of a total Philippine population of 7.5 million, making them a small minority.[7]

The desire of the pensionados to influence how Americans viewed their country also led to attempts in the Philippines to control the image of the Filipino. In 1914, the Philippine Assembly, the colony’s domestic legislature, passed a law banning the creation, reproduction, and dissemination of “photographs, slides, paintings, engravings or busts” of nude Filipinos.[8] The assembly passed the law because imperialists such as Worcester had long used images of unclothed Filipinas to convince Americans of the native “savagery.” These images sexualized the Filipina breast, and communicated that Filipinos required education on how to be “proper” and respectable.[9]

Yet even in the case of the Philippine Assembly’s prohibition of nude photographs, the intention was not to defend non-Christian groups. Instead, these attempts to protect the image of the Filipino were meant to distance the Christian Philippine elite from the image of the Filipino primitive. For Filipino elites, being Filipino meant being Christian, and they sought to replace the American narrative of Filipino identity with their own.

Citations

[1] For more on the St. Louis World's Fair of 1904, see Paul A. Kramer, Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines (The University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

[2] The Filipino, Washington, D.C.: The Filipino company, 1906.

[3] “Some Day or Other,” The Filipino 1, no. 2 (March 1906), 41.

[4] “Nuestro Programa,” The Filipino 1, no. 1 (January 1906), 34. The original Spanish text read: “...desde el Gobierno Americano ha tomado posesión de las Islas Filipinas, se han esparcido en todos los Estados de la Union versiones mas o menos inveridicas, se han publicado fotografias con mas o menos dosis de mala intencion, que tendiendo a desfigurar el verdadero estado de cosas en aquella apartadas regiones.”

[5] “Igorots and Americans,” The Filipino 1, no. 2 (March 1906): 4.

[6] Rafael Acosta, “Diversity of Filipino Languages,” The Filipino 1, no. 2 (March 1906): 16-17.

[7] United States Bureau of the Census, Census of the Philippine Islands, 14.

[8] Bill No. 590, of the Second Philippine Assembly. Diario de Sesiones de la Asamblea Filipina, Vol. 9, 1913 – 1914, pp. 832-4, from Charley Sullivan, "I hope to do something among the native races: Anthropology, Anthropometry and Photography in the American Racial Project in the Colonial Philippines," a paper at the conference Picturing Empire: Race and the Lives of the Photographs of Dean C. Worcester in the Philippines, University of Michigan, March 15, 2013, 27.

[9] Nerissa Balce, “The Filipina’s Breast: Savagery, Docility, and the Erotics of the American Empire,” Social Text 24, no. 2 87 (2006): 89–110.