Philippine Women in UM Archives

Finding Traces of Philippine Women

What can we learn about the lives of Philippine women by researching in UM archives? What positions did Philippine women have in society? What were their everyday lives like? What role did the UM play in shaping the experiences of Philippine women? In this post, we aim to explore these questions while considering the limitations of the archive. We read against the grain to examine the lives of Philippine women in relation to the UM and US imperialism in general. While recognizing the diversity of Philippine women in terms of race, ethnicity, language, region, and class, we hope to better understand how the colonial state—especially with the help of UM faculty and alumni—used gender and women to support their overall imperial objective.

Before colonialism (prior to Spanish rule in the sixteenth century), men and women across the Philippine archipelago held equal status on account of bilateral kinship.[1] Philippine women were responsible in fiscal matters and they also owned property. Their authority, especially in spiritual matters, also spanned over their communities, including their families.[2] However, 300 years of Spanish colonial rule and its Catholic influence left a strong patriarchal legacy in the Philippines, particularly among the elite.[3] Spanish customs defined women socially and politically in relation to men, specifically their husbands and fathers. Filipino nationalists further deployed this structural inequality by emphasizing women’s motherly qualities in their fight for independence in the late nineteenth century.[4] Women were stereotyped during this time as meek, timid, and subservient. In fact, these “feminine” traits were idealized within the patriarchal social structure.

Yet, the inferior social status of Philippine women did not mean that they suffered in silence. According to historian Maria Luisa Camagay, working women fought for better treatment.[5] These women worked in a variety of positions as cigarreras (tobacco factory workers), criadas (domestic workers), tenderas (store owners), vendadoras (vendors), costureras (seamstresses), bodadoras (embroiders), and mujeres públicas (sex workers). Women in these occupations engaged in labor organizing. Records indicate that they went on strike for better working conditions, salary raises, and to demand that supervisors be held accountable when found in violation of labor laws.[6] The actions of working women pushed back against existing gender stereotypes.

Nonetheless, the characterization of Philippine women as weak and timid carried into the US colonial period. Gender became an important means for the US to establish Philippine women as needing assistance from the Americans. Women’s issues, including freeing native women from the “oppression” of their own culture, became important for supporting US colonialism. By looking at UM archives, we can glimpse how the gendered colonial discourse affected Philippine women.

Philippine Women Through Photographs

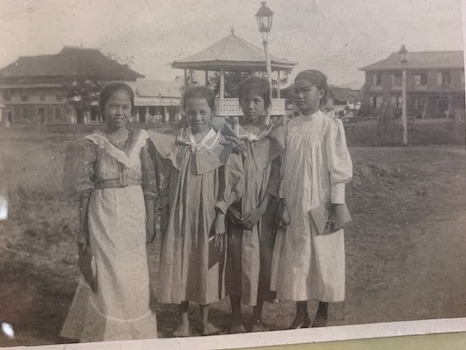

American women travelled to the Philippines in the late nineteenth century, when the Philippines became a US colony. These women sought educational opportunities and experiences through their missionary work. They were central to the goals of the US colonial project, working especially to “modernize” the Philippine people in addition to converting non-Christian tribes to Christianity.[7] These American missionaries took photographs (such as the one shown to the right) documenting their work and demonstrating their progress in their mission. Their photography focused on depicting Philippine women in Western clothing, posed in the style of the times.

The argument that they attempted to construct through photos was that Philippine women were easily assimilable into an American way of life. However, we should not assume that this is simply a case of blind assimilation, for equally evident is that they retained some Filipino styles of dress. Perhaps Filipinas recognized and took advantage of the opportunities presented to them if they appeared Western, though they did not entirely abandon their cultural customs. Viewing these images within the UM archive allows us to consider not only the image that American women (missionaries, and also teachers) wanted to create, but also to speculate about the motivations and reasoning of Philippine women.

Elite Philippine Women Study in the US

Another place that Philippine women appear in the UM archive is in student and educational records. The University of the Philippines, founded in 1908, became the site and source of many exchanges with the University of Michigan. The establishment of the Barbour Scholarship program in 1917 strengthened this institutional relationship further. Women from the Philippines came to the University of Michigan to study the sciences as well as pursue other interests. These women returned to the Philippines to become instructors and professors at the University of the Philippines, working in departments in the sciences and humanities. Some of these women became the heads of their departments, and others went on to become foreign service workers. Many helped other Philippine women to apply for the Barbour Scholarship.[8]

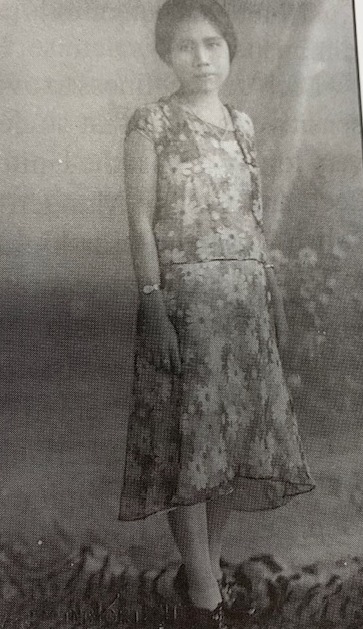

The publications and personal writing of Barbour Scholars helps us to understand the perspectives of some elite Philippine women during the US colonial period. Pura Santillan-Castrence (1905-2007) was a Barbour Scholar in 1930 from the Philippines. She later became a Filipino writer and diplomat. She was among the first Filipino writers to gain prominence writing in the English language. She studied chemistry and pharmacy at the University of the Philippines and taught there after her graduation. Her literary career began in the 1920s, and she became one of the leading Filipino essayists in the 20th century. Many of her essays were featured in Philippine Prose and Poetry, a widely studied high-school textbook. Additionally, she wrote columns for multiple national periodicals including the Manila Daily Bulletin. Her essays often emphasized Philippine femininity, marriage, motherhood, and responsibility to country and family.[9]

The Peace League

The work of American colonial programs, such as missionary projects and the Barbour scholarship, supported the goal of gendering US imperialism. Another program, known as the Peace League, contributed to this goal as well. The Peace League was established after the Philippine-American war uniting American and Philippine women in the work of promoting peace and calming Philippine revolutionary sentiment. Gender played a central role in the arguments of the Peace League. Government officials and pro-imperialist boosters began to publish newspapers and essays discussing how American rule would be more beneficial for Philippine women. Archival material from the Peace League points to the involvement of Filipinas in this broader project, though it is still unclear how Philippine women felt about their participation.

The archive mainly tells us about the goals of white American women. For example, former First Lady Helen Taft emphasized the importance unity with Philippine women in order to establish peace in the islands after the Philippine-American War.[10] She argued that peace was desired by all women for the sake of their loved ones and that women should play an equal role to men in the peacemaking process. Other American women also claimed that Filipinas had more rights and liberties under US rule compared to Spanish rule.[11] According to one American woman, known as Mrs. Traub, the Peace League was necessary to promote unity. She stated,

Every shot that kills, hits a mother’s heart, whether it be a Filipino or an American. Let the women join hands to end the war and introduce the beginning of the Twentieth Century, the noble and inspiring spectacle of a devoted band of women bringing peace and happiness to a devastated country.[12]

Mrs. Traub used gender to suggest that it was the Filipina’s duty to unite with American women in order to heal the country. While ignoring the cause of the country’s devastation, and the differences between American and Philippine women, Traub focused on essentializing womanhood and the desire for peace as a feminine characteristic. Philippine women emerge in Traub’s narrative, but only as objects who imitate the values and dispositions of white women in the Philippines.

Some archival records indicate that Philippine women agreed with the mission of the Peace League. According to a newspaper clipping retained by Russel Roy McPeek, 51 American women and 156 Filipino women were in attendance for an “enthusiastic” meeting. Details about the background or identities of the women were not provided in the newspaper. Given that this newspaper clipping, and related articles, were retained by an American suggests that the author of the article, as well as its publisher, were American. Considering these details, we have to wonder what 156 Filipina women were so “enthusiastic” about, and whether the message they received was the same that was given. Could the American perspective have misrepresented how Filipinas present in the meeting felt?

The American narrative of unity between American and Philippine women depended on the fact that the latter’s voices were rarely ever heard. The lack of Philippine voices supported the imperial narrative of “benevolent assimilation,” the ideological platform that claimed American rule was for the benefit of the Philippine people. Those that do emerge in the archive do so as objects of American discourse, or as elites or other powerful figures who benefitted from and formed close relationships with the American colonial state. With an archive such as this, which silences the voices of indigenous women, we have to use the gaps to question other possibilities that may not exist in the empirical evidence. These thought exercises can help us to consider how the colonized imagined alternatives to imperial rule.

Citations

[1] Ramona S. Tirona, “The Filipino woman: what she is and what she is not,” Philippine Herald (Dec 1920): 3–7.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Laura R. Prieto, "Bibles, Baseball and Butterfly Sleeves: Filipina Women and American Protestant Missions, 1900–1930," in Divine Domesticities: Christian Paradoxes in Asia and the Pacific, edited by Choi Hyaeweol and Jolly Margaret, (ANU Press, 2014).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Maria Luisa Camagay, Working Women of Manila in the 19th Century, (Philippines: University of the Philippines Press, 1995).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Laura R. Prieto, "Bibles, Baseball and Butterfly Sleeves: Filipina Women and American Protestant Missions, 1900–1930.”

[8] Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women Committee 1914-1983, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Alumni Files (1845-1978) - Pura Santilan, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[10] Russel Roy McPeek Papers. 1865-1945, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Mrs. Traub, Newspaper clipping, publication unknown. Russel Roy McPeek Papers, 1865-1945, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.