The Barbour Scholarship and US empire

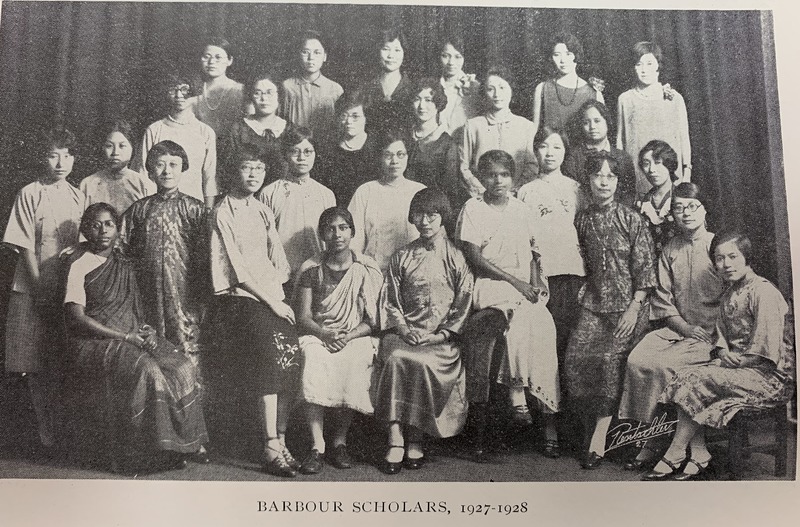

The Barbour Scholarship is one of the University of Michigan’s most prestigious educational programs. It was founded at the University of Michigan in 1917 by former Regent Levi Lewis Barbour, a Detroit lawyer, real estate developer, and philanthropist who was a Michigan alumnus.[1] Inspired by what he learned while travelling to Singapore, Shanghai, Beijing, Manchuria, and Tokyo, Barbour created his scholarship in order to contribute to the welfare of women from Asia. In China, he met doctors Shi Meiyu and Kang Cheng and in Japan he met Tomo Inouye. These were three women who studied medicine at the University of Michigan and provided much-needed medical services to their home countries.[2] Barbour Scholars were given the opportunity to study modern science, medicine, mathematics, and other academic disciplines that were considered critical to the development of their home countries.

When the Barbour Scholarship was first created, the program focused on three goals: 1) To help women from Asia attain status in their home countries; 2) To provide scientific and broad training that would prepare scholars for leadership positions and a life of service; and 3) To acquaint scholars from Asia with Western ideas and bridge East and West.[3]

While Levi Barbour’s vision led to a well-regarded and successful scholarship program that still exists today, it grew from a politics of empire. Barbour’s intention was not entirely altruistic, but it was also to influence the image of US foreign relations as benevolent and humanitarian. Promoting US education in Asia through this scholarship was connected to US imperial interests, as it focused on spreading American values and ideologies even while claiming to teach neutral subjects such as science and math. Barbour himself wrote in 1917 that if more “Japanese girls” were educated in the US, there would be no war with Japan. He connected the value of education with US foreign policy.

The scholarship program also rested on the idea that Western education was superior to what scholars would find in Asia. In a letter to University of Michigan President Hutchins, Barbour wrote: The idea of the Oriental girls’ scholarship is to bring girls from the Orient, give them an Occidental education and let them take back whatever they find good and assimilate the blessings among the people from which they come.[4]

Barbour’s celebration of “Occidental education” implies that Asian women were incapable of obtaining opportunities for social mobility in their home countries. He perpetuated a narrative in which the US, and specifically the Barbour scholarship program, would be the only way for these women to achieve success. Although there’s no denying the opportunities that the Barbour scholarship created for select individuals, the underlying narrative promoted white Americans as saviors who would uplift women from “underdeveloped” cultures.

Many of the Barbour scholars came from the Philippines.[5] In his 1937 paper “Barbour Scholars Around the World,” University of Michigan professor Carl Rufus noted that eight Filipina Barbour Scholar recipients had graduated and became faculty at the University of the Philippines.[6] These women included Encarnacion Alzona (History), Adelaida Bendana, Solita Camara, Esperanza Castro (Pharmaceutical Chemistry), Maria Lanzar (Political Science), Maria Pastrana, Pura Santillan (Modern Languages), and Carmen Velasquez.[7]

One of the more prominent recipients of the scholarship was Professor Maria Lanzar. The first Filipina recipient of the scholarship, Lanzar received the award in 1923 after earning her Master’s degree in the Philippines. At Michigan, Lanzar studied political science, with a focus on American sovereignty in the Philippines.[8] Lanzar received her PhD in Political Science in 1928, one of the first two Barbour Scholars to receive the degree.[9] Her dissertation, The Anti-Imperial League, took information from the personal files of American statesmen who took part in the colonial administration of the Philippines.[10] Upon returning to the Philippines, Lanzar joined the Political Science faculty at the University of the Philippines (UP). Lanzar additionally served as the Dean of Women at UP for several years and was an active member of the Philippine Association of University Women and the Philippine Academy of Social Sciences.[11] Moreover, she was an active member of the Barbour Scholarship Advisory Committee of the Philippine Islands.

At a time when segregation and Jim Crow laws were rampant throughout the US, it is not difficult to imagine that Barbour scholars faced racism while studying at the University of Michigan. Pura Santillan-Castrence, a Filipina Barbour Scholar turned author, published a book in 1930 titled As I See It, which discussed the relationship between Barbour scholars and white students. According to Santillan-Castrence,

I felt then that I was merely obeying the orders of the University of the Philippines to do further studies in the United States. I was somewhat frightened of the new adventure especially since I was snubbed by American students on the steamship and furthermore the Philippines was still under American rule at the time.

Santillan-Castrence revealed that the students she encountered in the US acted as though they were superior. She expressed fear and isolation through this memory. However, Pura Santillan-Castrence also discussed positive experiences in the US through the community that she developed at the University of Michigan. She noted that international students in particular bonded together because of their shared experience of feeling “isolated in the vast United States."[12] Upon reaching the US, the majority of the students formed communities with other Filipinos. A November 11, 1920 article in The Michigan Daily, for example, announced a meeting for all Filipino Students.[13]

She also described her close relationship with her American roommate:

While in university, we went to church together and had coffee and cigarettes together. I would often cook Filipino dishes like adobo and pansit for the group. Leeb took me several times to her home in Perrysburg, Ohio, where I got to know her parents and her brother Paul. There was a grapevine encircling their house and I gathered the fruit every morning which my Filipino tongue welcomed. I liked it when Leeb makes me re-tell stories or jokes she had heard from me, to show off her Filipino friend to her family members and relatives.[14]

The relationships that Santillan-Castrence made while studying in the US were just as important as the academic skills that she gained. As her account suggests, the Barbour scholarship presented challenges for women from places like the Philippines, but it also offered a unique opportunity. While critical of the treatment of Filipinos by white students—a result of the imperial and racial discourses of the time—Santillan-Castrence recounts how the experience personally changed her life.

The Barbour Scholarship was considered revolutionary in its time as it specifically focused on providing opportunities for women at a time when American women were not able to vote.[15] The scholarship was also significant given the broader international context, and the discourse that tied education to empire. Regent Barbour believed that the scholarship would be a way to foster understanding between East and West and that the University of Michigan had a pivotal role to play in global events.[16]

There were many similarities between the Barbour Scholarship and the Pensionado program. Both required their beneficiaries to return to their home countries to facilitate national growth. Moreover, the Filipino students in these programs came from privileged families.[17] The idea behind this was to use American education to create the next generation of leaders in the colony—individuals who would promote US interests. In this way, both the pensionado and the Barbour scholarship program were created in the context of US empire.

Both programs contributed to the idea of the Philippines as underdeveloped and Filipinos as needing US guidance and assistance.[18] This ultimately justified the US colonial project and neglected the inequalities that were caused by colonialism.

Citations

[1] Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women. 1922, 1924, 1926-1929, 1932, 1941. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[2] Donald S. Lopez, "In Celebration of the Barbour Scholarship; A Brief History of Asian Studies at the University of Michigan." October 23, 2017. Lecture given as part of the Barbour Centennial Celebration at Rackham Graduate School. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[3] Carl W. Rufus, “Barbour Scholars Around the World.” May 10, 1937. Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[4] Barbour Scholarship for Oriental Women: Records & History, University of Michigan, Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women Papers 1918-1969, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[5] The Philippines was one of the top four providers of Barbour Scholarship recipients, exceeded only by China, Japan, and India. See Singh, Avtar H. “Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women at the University of Michigan 1917-1955.” Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[6] Carl W. Rufus, “Barbour Scholars Around the World.” May 10, 1937. Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[7] Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women. 1922, 1924, 1926-1929, 1932, 1941. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[8] Carl W. Rufus, “Barbour Scholars Around the World.” May 10, 1937. Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[9] Carl W. Rufus, “Barbour Scholars Around the World.” May 10, 1937. Unpublished paper. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[10] Barbour Scholarships for Oriental Women. Letter to Former Scholars. Ann Arbor, May 1941. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[11] Alumni Files (1845-1978). Maria Lanzar. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[12] Pura Santillan Castrence, As I See It: Filipinos and the Philippines, (Sydney, Australia: Manila Prints, 2006).

[13] “All Filipino students meet in the basement of Lane Hall,” Michigan Daily, November 11 1920.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Barbour Scholars Centennial Celebration. Rackham Website.

[16] Donald S. Lopez, "In Celebration of the Barbour Scholarship; A Brief History of Asian Studies at the University of Michigan." October 23, 2017. Lecture given as part of the Barbour Centennial Celebration at Rackham Graduate School. Bentley Historical Library.

[17] Ibid.

[18] See Victor Román Mendoza, Metroimperial Intimacies: Fantasy, Racial-Sexual Governance, and the Philippines in U.S. Imperialism, 1899–1913 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2015).