The First Philippine Question

In the aftermath of the Spanish-American War, which ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1898, a heavily-debated question rose: what to do with the Philippines? While this topic was discussed across the nation and among elites, the University of Michigan was particularly given to debating it due to the large number of alumni involved in the imperialist expansion into the Philippines.

The early debate broke down into two sides: anti-imperialist and imperialist. Anti-Imperialists argued against expanding American influence in the Philippines. Imperialists sought to establish a civil society and train the Filipino population for self-governance.

Some anti-Imperialists preferred to remain distant from the Philippine project not because they believed in the right of the Filipino population to self-govern, but because they did not believe in the people themselves.[1] The views of anti-imperialists rejected the concept of the "White Man's Burden," a popular euphemism for imperialism derived from Rudyard Kipling's 1899 poem. Proponents of the White Man's Burden believed that white people had a moral responsibility to "civilize" the native inhabitants of the Philippines, who they believed to be inferior. Yet anti-imperialists contended that there was no point in attempting to save a population that did not have the capacity to be saved. In the late 19th century when these debates were occuring, it was not at all rare for Euro-Americans to believe that "race" was a natural category and that other races were biologically inferior. Scientific studies throughout the 19th century including Johann Friedrich Blumenbach's classification of human "races" reinforced the belief that race was biological and could be determined through objective observation. Studies of Filipinos during this time attempted to assign the native inhabitants to racial categories and ultimately stereotyped them as lazy, savage, effeminate, and violent.[2] Anti-imperialists reproduced these stereotypes in their writing and stood firm in the belief that Filipinos could never be equal to Euro-Americans.

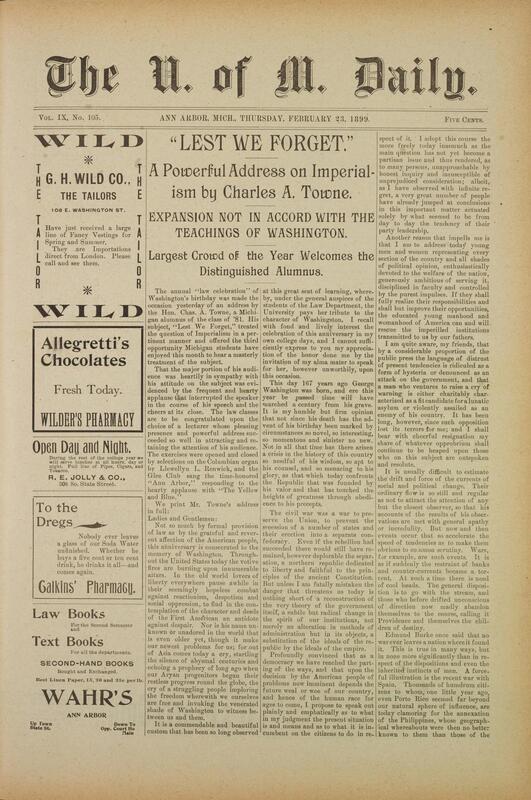

Anti-imperialists were adamant about the supremacy of Anglo-Saxon blood, yet their politics also hinged on the promotion of American democratic values. Charles A. Towne, alumni of the University of Michigan, was chosen by law students to speak at an annual law celebration in 1899 where he was met with applause while giving a speech on the Philippine Question titled “Lest We Forget.”[3] Towne explained how liberating Cuba during the Spanish-American War was a noble endeavor, but moving into the Philippines was an unnecessary move that threatened America’s democratic ideals:

Why, my friends, opportunities greater than all the orient, richer than 'barbaric pearl and gold,' awaits our enterprise, when it shall be disenthralled within the present limits of the Republic; and when that shall have been subdued the rest of this vast continent is ours by a law as certain in its result as it will be peaceable in its accomplishment. Were Washington alive today he would be to that extent an 'expansionist;' but we may be sure that he who left to posterity the priceless political testament of the 'Farewell Address' would as certainly and steadily opposed imperialism in the form of distant colonial dependency as he turned his back upon the offer of kingly power and 'put away the crown.[4]

Towne shared the belief of imperialists that America possessed the "God-given" right to expand and grow its territory and influence, as the founders intended. Yet he claimed that the founders did not intend for the US to partake in distant colonial rule similar to the British. He saw a line between expanding American territory and citizenship and creating nanny states that mirrored monarchies. Furthermore, anti-imperialists such as Towne held racist beliefs that prevented them from being open to the idea of integrating the Philippines into America. As this option was not up for negotiation, they saw the imperialist project only ending one way. Towne, as did many other anti-imperialists at Michigan, believed the Philippine project would not result in the expansion of US territory but rather in the creation of a dependent state. This state, they feared, would eventually leach American wealth and resources.

About a month later in 1899, the Michigan Daily printed an article by Professor B. Thompson, an imperialist. Thompson's viewpoint on US imperialism in the Philippines contrasted that of Towne. He used morality to argue that the US had an obligation to civilize the Filipinos, and he cited Thomas Jefferson in order to bolster his claims:

"We not only have the right to govern our Pacific possessions, but it is our moral duty to do so. When Jefferson said, 'governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed' he did not mean that we could not govern colonies justly without their consent. For he himself had slaves. He meant by that that no Anglo-Saxon had a right to govern any other Anglo-Saxon without his consent." [5]

Thompson defended the imperialist movement by reinforcing the belief that Filipinos, due to their race, were destined to be colonized. In arguing that it was unnecessary to obtain the consent of the governed in this case, Thompson naturalized the US mission in the Philippines while determining it to be a "moral duty." His writing echoed the White Man's Burden, which characterized Filipinos as incapable of self-governance and requiring the aid of the US in order to progress. Like many other imperialists before him, Thompson knew little of the social and political structure that organized Philippine communities long before colonial rule. His assumptions about Anglo-Saxon intellectual, moral, and cultural superiority reflected western scientific and cultural knowledge of his time.

In 1902, the Michigan Alumnus, another university publication, printed viewpoints that supported US imperialism by sharing some of the successes of the colonial administration. The publication focused on the experience of Euretta A. Hoyles, a white American school teacher based in Manila, Philippines.[6] Hoyles highlighted the progress of the colonial school system in spreading American values to Filipino children. The schools sang American tunes such as “Good morning, merry sunshine," and school schedules operated around American holidays such as Thanksgiving and George Washington’s birthday. Hoyles remarked, “Let the effort of the United States to educate this brown race be generously, patiently, radically carried out. A great contribution to the world's civilization must result therefrom."[7] Fueled from a sense of nationalism and racism, Hoyles reinforced the ideology behind the White Man's Burden. She believed that she was doing good work in attempting to mold Filipinos into "little" Americans.

Imperialists such as Hoyles and Thompson believed the Philippines presented unique opportunities to America in terms of practicing democratic and moral values. Their perspectives supported other imperialist arguments that centered on the strategic military and economic advantages that colonization of the Asia-Pacific region created. As scholars have pointed out, one of the main arguments of imperialists more generally was the vision of the Philippines as a market for American goods and Filipinos as "cheap labor" to lower production costs and increase profit.

The records of the imperialist debates in Michigan reveal a variety of opinions on the costs and benefits of US expansion in the Philippines. Yet within the collection of Michigan Daily articles that discussed the Philippine question, professors, students, and alumni did not consult Filipinos in advocating for their political views. The presumption of professor B. Thompson that it was unnecessary to obtain the consent of the Philippine inhabitants was indicative of a larger pattern within these debates. Despite the fact that US imperialism directly affected Filipinos, Euro-American members of the University of Michigan community deliberately omitted their voices. The archival silences on Philippine perspectives reflect the dominant view of Euro-American scholars and community members debating imperialism during this time. They viewed Filipinos as uncivilized, incapable of self-governance, and racially inferior.

In the end, the imperialists won the debate. The US assumed political control over the Philippine archipelago and the Philippine question was put to rest. It was not until the early 1930s that the question of US colonial rule re-emerged. During this time, a second Philippine debate rose within the Michigan Daily. The main question of the 1930s debate was: should Filipinos be granted their independence?

Citations

[1] Kristin L. Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Michigan Daily, February 23, 1899, Vol. 9, Iss. 105, Ed. 1, the Michigan Daily Digital Archives.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Michigan Daily, March 2, 1899, Vol. 9, Iss. 111, Ed. 1, the Michigan Daily Digital Archives.

[6] Michigan Alumnus, Vol 8, 1901-1902, pg 396-401, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[7] Ibid.