Content Warning: This page contains ableist language and photographs of patients with leprosy.

The Island of No Return

Heiser and Culion

The Culion Leper Colony was first founded in 1902 during the time of the American Colonization of the Philippines by Dr. Victor G. Heiser. Heiser was appointed as the Director of Health of the Philippines under Secretary of the Interior, Dean C. Worcester in 1905. At the time, leprosy had no known cure and Heiser estimated it affected more than six thousand people across the archipelago with twelve hundred more contracting the disease each year.[1] Heiser utilized a segregation policy to protect the healthy by isolating the “sick”. Heiser remarked, “this policy at first sight seems to impose many hardships upon the lepers themselves and their immediate relatives and friends, but it is believed to be fully justified not only by the fact that hundreds may be annually saved from contracting leprosy, but also that the victims may be given as pleasant a life as possible.”[2]

Heiser sought to accomplish “exiling” all Filipinos with leprosy to Culion. Passed on September 12, 1907, Act 1711 of the Philippine Commission gave the Director of Health the responsibility for implementing the segregation program. The law stated that, “the Director of Health and his authorized agents are hereby empowered to cause to be apprehended, and detained, isolated, segregated, or confined, all leprous persons in the Philippine Islands.”[3] Following the implementation of Act 1711, the local health inspectors that were responsible for taking in those with leprosy became one of the most feared government officers in the region. Those being taken to Culion would leave behind their homes, families, and communities, knowing that they would most likely never return.

Prisoners of Hope

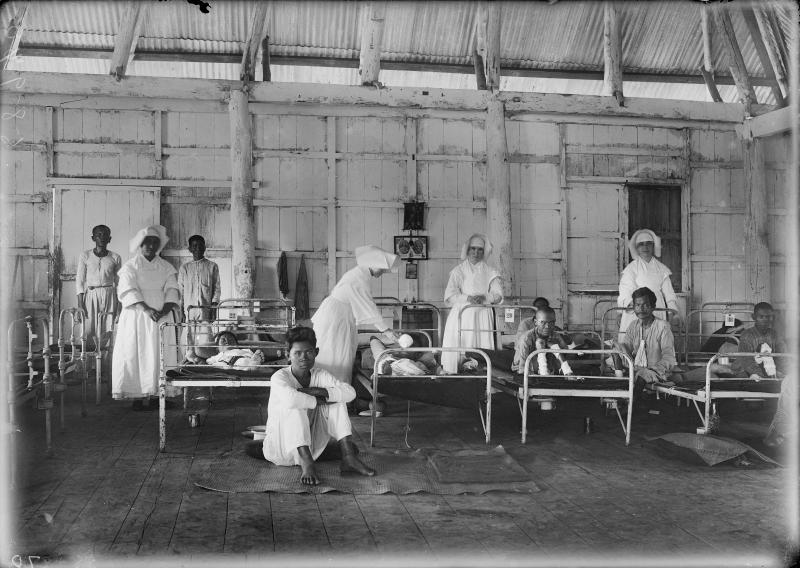

Culion first started with 370 patients in 1906 and grew to over 5,000 in just five years of its establishment. The patients with leprosy were known as “prisoners of hope”, being taken to an island where they were promised better living conditions and treatment for their condition. Worcester claimed that Culion was a, “healthful sanitary town with good streets, excellent water and sewer systems, modern buildings, and a first-class hospital… they are well fed and cared for. The only hardship they suffer is separation.”[4]

The “Island of Hope” Heiser promised was better known amongst Filipinos as “La Isla de Dolor”, or “the Island of Pain.”[5] About sixty percent of the four thousand and more admitted to Culion died within the first four years. Some patients wrote to the Manila newspapers complaining about the neglect they felt. Protests from the patients began to lessen the efficacy of Worcester and Heiser’s view of Culion being an “Island of Hope”. The food was insufficient, housing was overcrowded, and the police were oppressive.[6] With many articles during this time applauding Heiser and glorifying the island, a 1912 Manila Daily Bulletin article stands out with criticism of the Culion management. Among many things, the article points out that the transportation of the patients to Culion was executed horrifically, the food is deficient in both quantity and quality, and the number of doctors and nurses is insufficient to meet the needs of the colony.[7] Funding was being spent on unnecessary things like the construction of a concrete theater with a “magnificent staircase.”[8] The Assembly Committee declared three basic defects that existed at Culion; “that scientific measures for the treatment of the lepers have not been adopted; that maladministration of the colony both as regards funds for construction and food for lepers, and that no measures tending toward the social development of the colonists have been undertaken.”[9]

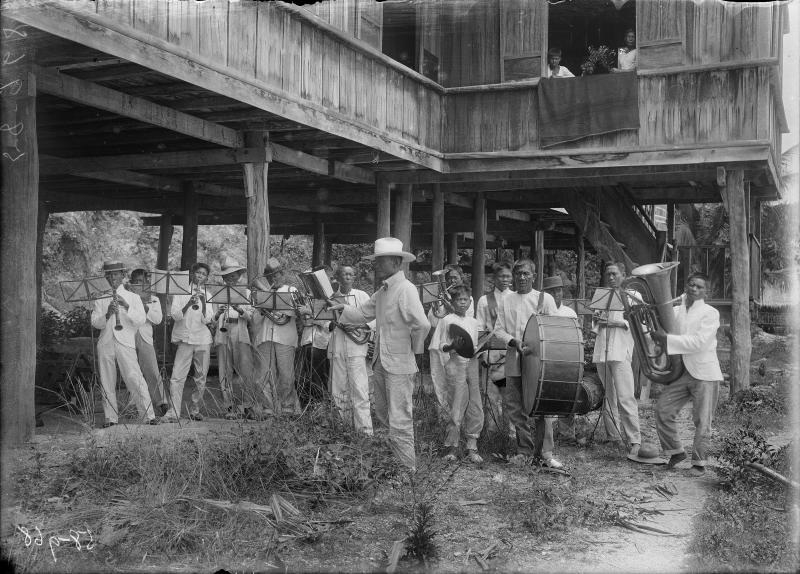

Attempts at maintaining civic pride were made. Some tried to raise cattle, some tried to start sugar plantations, and others would carry out the typical duties of cleaning, cooking, and repairing. They elected their own mayor and council and even formed a "leper band" to put on occasional performances.[10] The effort to establish a sense of normalcy on the island seemed to just be placing a bandaid over their situation. Heiser once expressed that, “usually the leper is so depressed that he takes no interest in anything at all.”[11] What united them the most was perhaps the collective struggle they faced of isolation, and the little hope they held onto that they may be one of the lucky ones to heal and recover.

Escaping the Island of No Return

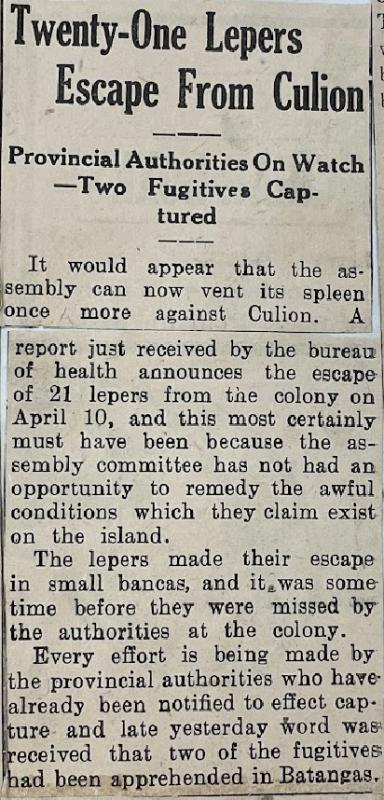

Another article from the Manila Daily Bulletin on April 22, 1914, highlighted twenty-one patients that escaped from Culion.[12] They were not the first and certainly not the last to make an attempt to escape. In fact, almost 500 escaped between the years 1906 and 1916.[13] The continued effort to escape over the years conveys that not everyone was truly satisfied with life on the island. The article states that the Assembly Committee “can now vent its spleen once more against Culion,” with the news of patients escaping.[14] Concerns from the public were made apparent but it was not enough to better the situation in the colony at the time. It was only after Heiser resigned as director of health in 1915 that he became more attentive to the ongoing advancements in the Philippines alongside appointed governor-general Leonard Wood. He influenced Wood to allocate more than one-third of the Philippines’ health budget to Culion improving medical staffing and treatment and increasing the number of paroles.[15] It is unclear why improvements were made only after Heiser left his position, but his obsession with imposing colonial medicine on the Philippines continued to persist.

Language and Stigma

While this article brings to light public concerns about Culion, the language used continues to show how people with leprosy were viewed. Words like “fugitives” and “apprehended” used to describe those who escaped seem to contribute to the idea of Culion being an island for banishment and confinement. While we cannot say precisely what continued to push people to escape over the years, the isolation experienced and the stigma around the disease most likely played a role in those decisions. Before ships started to collect people with leprosy and take them to Culion, the government began a campaign to “educate” regions in the Philippines about leprosy and what life would be like on the island. Heiser wanted to teach Filipinos that, “the leper who concealed his disease was a constant and deadly menace to the community in which he lived.”[16] This “education campaign” seemed to be more of a scare tactic than anything else. Heiser once reflected in his journal that, “the keynote to success [is] to educate the masses to a fear of the disease.”[17]

Historically, the word “leper” represented someone with leprosy. However, with the limited knowledge of the disease at the time and the stigma enabled by Heiser, the use of the word “leper” was offensive and derogatory. Leprosy was thought to be an extremely contagious disease, and with the scare tactics in place, the term “leper” signified someone that should be avoided. It represented people as “outcasts”, and with the establishment of Culion, those with leprosy quite literally became “outcasts” as they were sent to the island to be isolated from the rest of society.

Life at Culion did not appear to be desirable. Patients were reduced to the term “leper.” They became guinea pigs and were subject to medical treatment in an effort to find a cure. They were expected to continue living a normal life and contribute to their community while living with a disease that resulted in the “contraction of the limbs, destruction of tissue, losses of fingers and toes… and general debility.”[18] Culion was another product of American imperialism. Warwick Anderson, a current professor in the Department of History at the University of Sydney, wrote in his book Colonial Pathologies that Culion, “was predicated on a form of biological and civic transformation in which the contaminated became hygienic, and ‘savages’ might become social citizens.”[19]

Heiser received much praise for his work in the Philippines during his time as the Director of Health from newspapers like The Cablenews-American describing his work as “heroic.”[20] However, it is important to approach the American sanitarian policies imposed on the Philippines with a critical mind. We can acknowledge that “modern science” and sanitation may have improved the overall health of the Philippines at the time. Still, it is vital that we center Filipino voices and those advocating for their voices to be heard to examine how truly ethical and sustainable the policies imposed by the U.S. were.

Citations

[1] Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Duke University Press, 2006), 164.

[2] Ibid, 165.

[3] “Act No. 1711: An Act Providing for the Apprehension, Detention, Segregation, and Treatment of Lepers in the Philippine Islands.” Official Gazette 5, no. 41 (1907): 622.

[4] Yasmin D. Arquiza, Culion Island: A Leper Colony's 100-year Journey Toward Healing (Culion Foundation, Inc., 2003), 60.

[5] Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Duke University Press, 2006), 173.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Manila Daily Bulletin, Mar. 4, 1914,” vol. 6, Worcester’s Philippine Collection, Clippings, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Duke University Press, 2006), 172.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Manila Daily Bulletin, Mar. 4, 1914,” vol. 6, Worcester’s Philippine Collection, Clippings, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan.

[13] Yasmin D. Arquiza, Culion Island: A Leper Colony's 100-year Journey Toward Healing (Culion Foundation, Inc., 2003), 174.

[14] “Manila Daily Bulletin, Apr. 22, 1914,” vol. 6, Worcester’s Philippine Collection, Clippings, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan.

[15] Warwick Anderson, Colonial Pathologies: American Tropical Medicine, Race, and Hygiene in the Philippines (Duke University Press, 2006), 175.

[16] Ibid, 166.

[17] Ibid, 166.

[18] Ibid, 172.

[19] Ibid, 159.

[20] “The Cablenews-American, Jul. 15, 1914,” vol. 6, Worcester’s Philippine Collection, Clippings, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan.