Content Warning: This page contains graphic descriptions of war, violence, and racist language.

The War in Samar: Moral Justification for Colonial Aggression

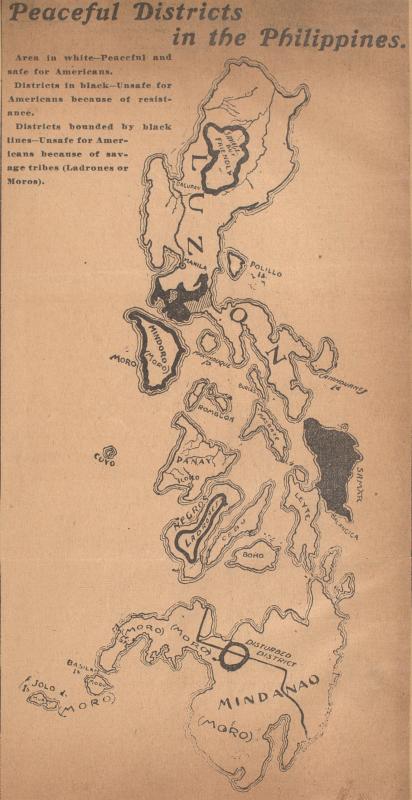

Samar is the third largest island in the Philippines. The island is mainly inhabited by the Waray-waray people, the fourth largest ethnolinguistic group in the Philippines. The Philippine archives at the Clements Library and the Special Collections Research Center at the University of Michigan provides records and firsthand accounts of the United States’ occupation of the Philippines, particularly in the Samar and Leyte region, as well as descriptions of various revolutionary operations in those areas during 1900-1902.

As a whole, the Philippine-American war is often viewed through a monolithic lens, or almost entirely focused on the NCR (National Capital Region). As a symptom of the legacy of American colonialism and the American-centric narrative that has dominated discourse on this topic, regional histories have been neglected and overlooked. By analyzing individual regional identities during this era, the experience and voices of Filipinos can be centered in a topic with such saturation of the perspective of colonial figures. The Samar region in particular is a noteworthy example because of its lasting region-wide resistance to American occupation during the later years of the war, and the significant threat that Samareño forces posed to the American colonial empire. Through studying the impact and leadership of key figures such as Vicente Lukban, connecting the cultural background of Samar to its strength and organization during the war, and analyzing the pattern of American brutality in the region, it is possible to understand why there was so much concentrated military action in this specific region and add more nuance to a landscape that has historically been dominated by American colonial perspectives.

General Vicente Lukban: Opposing US Dominance

General Vicente Lukban was a key figure in the Philippine Revolution, serving as one of Emilio Aguinaldo’s officers. After the war, he went into exile with the Hong Kong Junta, a group of Filipino revolutionaries who had fled to Hong Kong following the end of the Philippine Revolution.[1] During his time in Hong Kong, he studied and mastered various facets of military science, including war strategy and tactics. In 1899, during the onset of the Philippine-American war, he was proclaimed governor of Samar with little to no resistance.[2] Throughout Samar, he established various training camps and arsenals in anticipation of the arrival of US forces. To further coordinate the region, he divided it into 3 areas headed by Col. Narciso Abuke, Col. Claro Guevara, and Capt. Eugenio Daza.

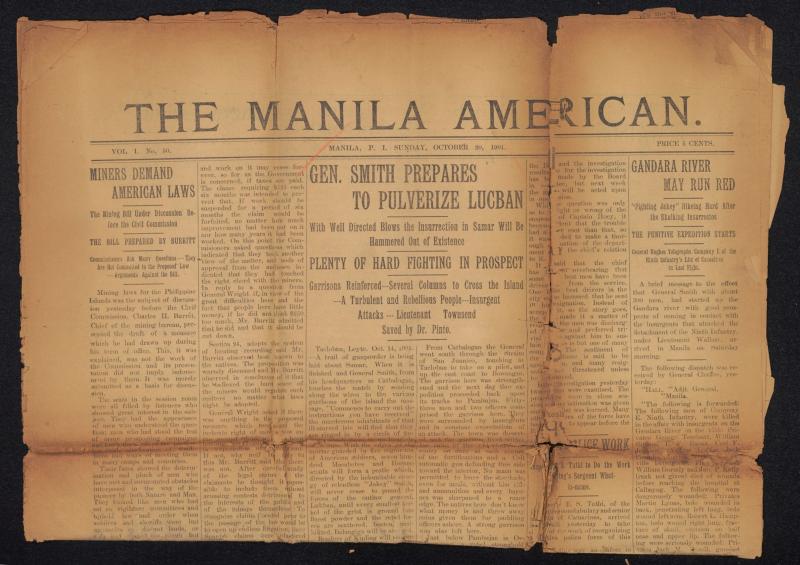

Initially, the United States anticipated easily gaining control of the region as they had with other regions of the Philippines, with ambitious plans of “energetically [crushing] Gen. Lukban.”[3] While many anticipated an easy defeat and surrender from Lukban, he proved himself to be a formidable opponent because of his leadership and strategy. The underestimation of Lukban and his organized revolutionary efforts became evident to the United States shortly after their arrival in Samar. Not long after the arrival of the Americans, one news source stated, “the present campaign in the island of Samar is one of the most difficult undertaken this year.”[4]

As previously explained in Identifying an Enemy, the United States used racist and harmful rhetoric to morally justify their colonization of the Philippines. Following this pattern, as the United States forces struggled to defeat troops in Samar, the media turned to vilify Lukban, perhaps to overcompensate for their earlier misplacement of confidence and justify their aggressive occupation of the region. According to one news source, “Gen. Lukban, the chief insurgent leader… ruled with such a firm and cruel hand that it is hard to make natives believe his power is broken, and naturally they are slow to transfer their allegiance to the United States.” Furthermore, it was described that “inhabitants of Samar [were] terrorized by Gen. Lukban…” [5] This source uses the term “insurgent” to delegitimize Lukban’s authority over the region as well as characterizes the native population as incapable of independent thought.

By no means a perfect leader, the claims of him terrorizing the Filipinos were sensationalized in order to feed the narrative that resistance against the United States was unacceptable. Lukban remains an incredibly nuanced figure in Philippine history. For example, Lukban was anti-friar, and known to have incited friction with the Catholic clergy with aims to rid the Filipino clergy of Spanish influence and control. This included antagonizing Francisican priests and coercing them to agree to his various changes to the structure of parishes in Samar. That many Samareño priests also supported his revolutionary works shows just how effectively he was able to galvanize people towards the overall goal of resisting American power.[6] Additionally, while support for Lukban was widespread, amongst regional leaders and chiefs,[7] Lukban himself sometimes resorted to violent means to like burning towns and killing American sympathizers to keep control over Samar.[8] The United States was no stranger to these tactics either, but the vilification of Lukban helped promote the colonial narrative and give justification to heightened aggression in the Samar region.

Waray Waray Hindi Tatakas: A Cultural Legacy of Revolution

To better understand the motives and the strengths of the revolutionary movement in Samar, it is imperative to analyze the cultural background of the Waray people. In the Philippines, the term “bayanihan” refers to the communal value of unity and cooperation. The Waray equivalent of this is “pinaktasi'', which exemplifies the spirit of communal action. This phrase best encapsulates the core values of the Waray culture: freedom, community, and solidarity. As Tomas Andres explains, “[A] characteristic of the Waray is … the feeling of being bound as a clan, tribe or group.”[9] This shared value of collective unity and the high regard of the greater good of the community is perhaps one of the most significant sources of strength for the revolutionary movements during the Philippine-American War. Because of this ingrained cultural sentiment of collectivity, Samareños were effectively able to organize their troops and maintain such a strong hold over the region, posing a serious threat to American forces who attempted to take over the region. This also demonstrates why the people of Samar did not easily give their allegiance to the United States. The sense of belonging to the region and the strong link to cultural identity vastly outweighed any possible “benefits'' that Americans could have brought.

As described in Filipinos During the War, one tactic commonly employed by the United States military was the burning of crops, houses, and entire towns to force Filipinos to accept American colonization. This destruction, however, had immense cultural implications in Samar. Not only did the burning of crops take away important resources and food for the Samar people, but it was also a sign of immense disrespect for the Waray culture. According to folk practices in Samar, there are many rituals and practices that celebrate rice and camote - crops that were often subjected to burning. Prior to colonization, rice farmers gave thanks to elemental gods as a thanksgiving for bountiful rice. The crops and the fields themselves were believed to be connected to deceased ancestors and spirits who protected the crops.[10] Therefore, the burning of crops signified something greater than merely taking away food - it showed the destruction of culture, insensitivity towards indigenous practices, and the notion that Filipino traditions were somehow “insignificant” or “unimportant”. This alone could provide ample motivation for organization against American occupation because of the callousness towards the Waray culture. The burning of crops not only inflicted immense harm to the Samar population, but it also drove Filipinos further into opposition to American occupation, strengthening the power of Filipino revolutionary forces.

US Occupation and the Perseverance of Resistance

As the war waged on, US military shortages became rampant, especially of rope shortages during the later years. Because Samar was a hub for hemp production, the occupation of this island was integral to the US to address its shortages.[11] In 1900, the 43rd Infantry were ordered to occupy Calbayog and Catbalogan. There, they were met by Lukban’s forces, who were eventually forced to retreat to the interior, more mountainous areas.[12]

In their attempt at “benevolent assimilation”, the United States began various projects regarding the education and the infrastructure of the native population. In one letter, Corporal Edwin A. Rowe, a volunteer of the 43rd Infantry, describes a snapshot of these efforts. He says, “the Major is now hiring natives and chinamen to clean up and beautify the city.” Later in the same letter, however, he states that “Natives are doing the work and soldiers are bossing,” and describes the implementation of a curfew on the native population.[13] This suggests that despite the facade of benefitting the people of Samar, many of these projects subjected them to forced labor, thus stripping them of their autonomy even on their own land.

Eventually, the Americans realized that this approach at attempting to “win” the support of the Waray people proved futile. At first, there was hesitancy to use more violent measures because of potential backlash from American opposition and anti-imperialists.[14] However with increasing pressure from guerilla forces, the United States turned to more violent policies in order to force the native population to their side. These measures included the burning of houses, entire villages, and crops to “punish” the people of Samar for not accepting American occupation.[15]

Descriptions of these actions can be seen through Lieutenant Harry M. Dey’s accounts of the various campaigns he participated in. He describes these campaigns as “taking possession” of the different areas he travels through. This rhetoric exemplifies the general American view of the Philippines. Rather than being a distinct nation with its own agency, the United States believed it to be something for its taking, something that inherently belonged to the Americans. He also writes about his encounters with Filipino revolutionaries. According to Dey,

[T]he insurgents fled leaving large quantities of stores behind, this together with their quarters and every house in the town was burned. On the return down the river large quantities of stores were found in houses along the river these together with the houses were burned, also the towns of Bayog and Bigo were destroyed.[16]

The callousness and indifference evident in these accounts suggest that this practice had become normalized and almost routine: not used as a last resort, but rather for pure intimidation. It removes all humanity from Samareños because of the lack of regard for the aftermath of the towns’ residents and civilians and their wellbeing. Rather than viewing Samareños as autonomous people, capable of choosing their own allegiances, American forces punished them and attempted to force them into pacificity.

“The Balangiga Massacre”

In August 1901, Company C of the 9th U.S. Infantry Regiment arrived in Balangiga and were greeted by the mayor, Pedro Abayan. During the American occupation of Balangiga, the Americans were initially well received and tended to fraternize with the local population. However, this fragile coexistence was bound to shatter. As time went on, allegations of various sexual harassment against American soldiers arose. The last straw was an incident where American soldiers publicly harassed a young girl and were subsequently attacked by her brothers.[17] This prompted Captain Connell of Company C to unjustly detain the male population of Balangiga. As this rapport between American forces and the people of Balangiga continued to break down, Samareño troops began planning for retaliation.

Finally, in September 1901, guerilla forces entered the town. They seized American weapons and rushed towards Connell’s unarmed men in the morning. According to one newspaper source, “Insurgents secured all company supplies and rifles except 3. Company was attacked during breakfast morning Sept. 28.” [18]

The aftermath of this attack proved to be disastrous for the inhabitants of Samar. Following this event, thousands of soldiers were sent to Samar in retaliation. General Jacob H. Smith assumed command of operations in Samar later that year. Infamous for his cruelty, he ordered to “kill and burn” and turn Samar into “a howling wilderness”.[19] The press relentlessly attacked the region and its people as well. To further the American colonial narrative and justify the violence in the region, the people of Samar were constantly belittled and dehumanized. In one source, it is stated that, “Every native is a possible enemy if it is interest to be so. Prompt measures and an active prosecution of the campaign simultaneously all over the island will cool their enthusiasm”.[20] Furthermore, by referring to the events in Balangiga as a “massacre” and not portraying it as a coordinated response to American occupation in Samar, it was possible for the United States to mask their role in the agitation of the native population through their portrayal of American soldiers as victims, hide their military shortcomings compared to the Filipino forces through the delegitimization of the capabilities of Filipinos, and justify an extremely violent approach to finally gaining control over Samar. The Balangiga attack was the catalyst for heightened violence in the region, with American forces ruthlessly moving through the island, creating a path of violence and brutality. In hopes that this aggression would be the final blow to subject Samar to colonial control, Americans believed that, “It must be a war of extermination. Then they will come to terms.”[21]

The “Balangiga Massacre” is often considered one of the most disastrous losses for the United States military during the Philippine-American War. While at the time this event was considered rather unprompted and unprovoked, looking at the history of occupation in Samar, the increased military response due to Lukban’s organization, and the cultural norms of cooperativity within the island, it is evident to see that the “Balangiga Massacre” is the culmination of Samareño revolutionary efforts and display of strength against the United States. Therefore, it cannot be considered as a single, isolated incident, but rather as a symbol of the Philippine-American War in Samar as a whole: a war where Filipino strength and capability were severely underestimated and later recontextualized to paint Americans as victims, thus ridding them of the atrocities committed in the Philippines and serving as moral justification to heighten brutalities committed towards Filipinos.

Citations

[1] Spencer C. Tucker, The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO 2009), 345.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Pg. 31, Vol. 5, Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[4] Pg. 32, Vol. 5, Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[5] Pg. 44, Vol. 5, Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[6] Rolando O. Borrinaga, The Balangiga Conflict Revisited (New Day Publishers 2003), 5.

[7] Ibid, 8.

[8] Spencer C. Tucker, The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, 606.

[9] Tomas D. Andres, Understanding the Values of Eastern Visayas (Giraffe Books), 23.

[10] Gregorio C. Luangco, Folk Practices and Beliefs of Leyte and Samar (Divine Word University of Tacloban 1982), 17-18.

[11] Spencer C. Tucker, The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, 567.

[12] Ibid, 606.

[13] Item 1, Folder 4, Box 1, Edwin A. Rowe Papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[14] Thomas A. Bruno, “The Violent End of Insurgency on Samar 1901-1902.” Army History, no. 79 (2011): 32.

[15] Ibid, 34.

[16] Soldier’s Narratives - Journal (Nov. 13, 1899-July 6, 1901), Box 1, Philippine-American War in Leyte and Samar, Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan.

[17] Rolando O. Borrinaga, The Balangiga Conflict Revisited, 65-70.

[18] Pg. 71, Vol. 5, Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[19] Thomas A. Bruno, “The Violent End,” 39.

[20] Pg. 73, Vol. 5, Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[21] Ibid.