Policing the Philippines pt. 2

This is a continued post under the series titled “Policing the Philippines” please reference first post for more information.

The contrast between the photos of smiling Americans and dead Filipino revolutionary fighters could be found in other archival material as well. In the papers belonging to Harry Hill Bandholtz, a professor from what is known today as Michigan State University, such a juxtaposition also appears [1]. Pictures of Filipino families are mixed with photographs documenting the hangings of Filipino men who were found guilty by American courts. In this post, we will go over the policing and judicial sanctioning of the criminalization of Filipino actions by American courts.

There were many reasons as to why thousands of Filipino men and women were tried and found guilty in the US-established courts in the Philippines and under US law, and the creation of the American judicial system in the Philippines does not lay far out Michigan’s sphere of influence. George A. Malcolm, a 1906 graduate from the University of Michigan’s Law School established the law school of the University of the Philippines and became its Dean in 1912 [2]. Five years after becoming Dean, Malcolm was appointed by President Woodrow Wilson to Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines. In this role, Malcolm effectively institutionalized the imperial ideologies of other “Michigan Men” like Dean Worcester, James LeRoy, and Owen Tomlinson [3].

While serving as the Dean of the Law School, Malcolm was tasked with evaluating the capability of Filipinos to “self-govern” [4]. In his letter to President Wilson, he explains that he would give up his position as Dean should a Filipino suited for his position be made available [5]. In the library lay numerous cases that had reached the Philippines Supreme Court that Malcolm legally weighed in on. Many of the cases were concerned with heroin and cocaine use or trading [6]. Filipino men received a harsh punishment for owning, using, or even passing by property that was associated with opium.

Although Malcolm eagerly prosecuted Filipinos who were caught in possession of opium, US laws in the Philippines, and even nationally, were at first not opposed to heroin. As historians have noted, a combination of factors led to the prohibition of opium, among which were protestations by missionaries, who were worried about the effects of consumption in their mission fields and on potential converts. Likewise, in the Philippines, missionaries also played a role, generating knowledge about Filipinos and regulating their day to day lives. There was an ostensibly moral element to policing.

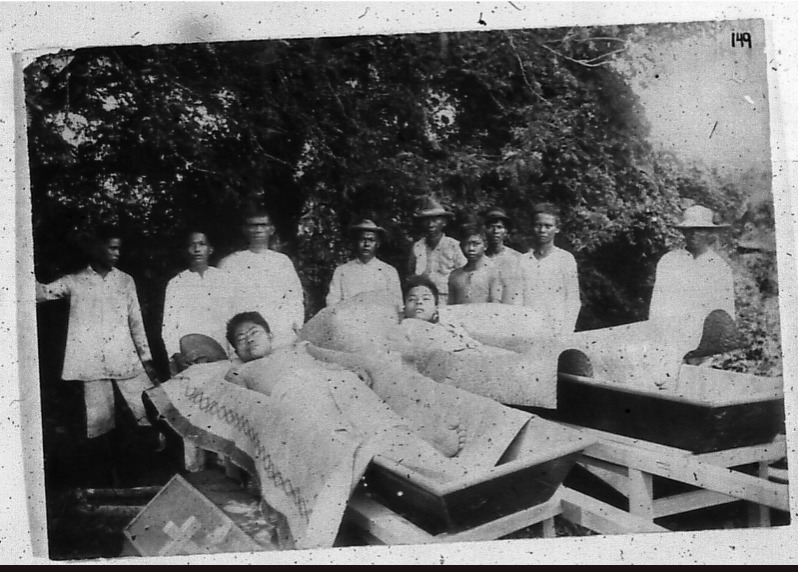

Through the creation of a US-based judicial system in the Philippines left unchecked, the courts used their own discretion to determine the right punishment for their so-called “little brown brothers.” While opium use was sometimes met with decades of jail time, rape and murder were given life sentences or death penalties. The latter fate would be the case of Leoncio Tabordan [7]. Under the US-established “Headquarters Department of Southern Luzon,” Tabordan was found guilty of torturing and killing another Filipino by the name of Tomas Ragudo [8]. Bandholtz documented American soldiers going to Tabordan’s home to take him, and a paper after his hanging documenting his death [9]. It is unclear if the soldiers at Tabordan’s door were arresting him or taking him to the place of his execution. If it was the latter, then that was the last photo of Tabordan taken while he was alive.

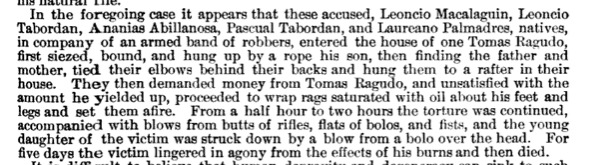

In the “Affairs in the Philippine Islands, Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines of the United States Senate” of April 02, 1902 there is a description of the torture that Tabordan and other men allegedly committed [10]. It is unknown how such exact details were obtained if they had actually happened.

The torture and alleged violence committed by the Filipino men are depicted as animalistic and malicious. The identification of both men as “natives” after their names distinguishes them and makes their nativeness synonymous with such gruesome actions.

The Senate hearing on the affairs in the Philippines Islands document is packed with hundreds of other court orders in which the US found these men guilty under its own law [11]. Indeed, the imperial archive is replete with materials depicting--often visually and sometimes graphically--colonial law and order. Within Tomlinson’s collected images there are also photographs of Filipino men caught headhunting held in handcuffs. In other cases, Bandholtz captured pictures of dead men’s bodies after they were hanged.

Colonizing the Philippines was a multilateral process that included the US creating a judicial system in the Philippines in which it could put Filipinos on trial, determine their level of innocence or guilt, and have their rulings uncontested. In addition to random beatings, torture, and rapes, were if the criminalization and the dehumanization of Filipinos was sanctioned by the US established judicial system. Indeed, as many historians have argued, the American colonial Philippines was a laboratory for the uneven administration of law and punishment. Similar practices were uncovered in the US occupation of Iraq as well, specifically through the case of Abu Ghraib. Iraqi men were found guilty and tortured in Abu Ghraib without a trail, and only under the suspicion of being terrorists.

Citations:

1. Harry H. Bandholtz Papers Microform 1890-1937, 1899-1925, Roll 11., Harry H. Bandholtz Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

2. George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

3. George A. Malcolm papers 1896-1965, Decisions 1917-1918, Box 5., George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

4. Ibid.

5. George A. Malcolm papers 1896-1965, Opinions 1913, Box 5., George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

6. George A. Malcolm papers 1896-1965, Decisions 1917-1918, Box 5., George A. Malcolm papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

7. Senate, U. S. "Affairs in the Philippine Islands: Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines of the United States Senate." Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (1902).

8. Ibid.

9. Harry H. Bandholtz Papers Microform 1890-1937, 1899-1925, Roll 11., Harry H. Bandholtz Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

10. Senate, U. S. "Affairs in the Philippine Islands: Hearings before the Committee on the Philippines of the United States Senate." Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (1902).

11. Ibid.