Creating the Moro Subject: Resistance and Pacification

In the pre-colonial era, Islam spread to the southern Philippines through trade networks, connecting diverse sultanates and ethnolinguistic groups. The people of this region eventually became known as Moros, the region, Bangsamoro. Today, the Moro people represent the largest Muslim and non-Christian population in the Philippines, comprising 5% of the country’s population. The Philippine archives at the Bentley Historical Library discuss the Moro people in records about the Philippine-American War. US military officers and soldiers from Michigan reported on what they called the “Moro Rebellion” between 1903-1913, providing a glimpse of the role of Michigan Men in the war and colonization of the Moro people. Before we get into the details of US military rule in the southern Philippines, it is important to understand the history of the Moro struggle beginning with Spanish colonialism.

Moro Resistance to Spanish Colonial Rule

Well before the arrival of the Americans, the Moro people fought to maintain their culture and independence from Spanish colonialism beginning in the early sixteenth century. The Spanish considered the Moros a threat to their Catholic mission in the Philippines and worked to prevent the spread of Islam throughout the archipelago. In fact, the name “Moro” is a Spanish term for “Moors,” referring to the Muslims who ruled the Iberian Peninsula from 711-1492. The Spanish expelled the Moors and reclaimed the peninsula during an event called the Spanish Reconquista (or "reconquest"). The Reconquista happened not too long before the Spanish colonized the Philippines, which influenced their determination to make the archipelago a Christian rather than a Muslim colony. According to historian Michael C. Hawkins, "The epithet ‘Moro’ embodied all the antipathies and condescension associated with the Spaniards’ expulsion of Muslim ‘Moors’ from Southern Spain.”[1] However, the Moro people of the Philippines stood their ground and resisted the Spanish vision of a Catholic colony.

After more than 300 years of Spanish colonial rule, the Moros were never fully conquered, nor were they Christianized. Their defiance was fueled in part due to the disrespect of some Spanish colonists towards Moro culture. According to historian Cesar Majul, the Moro resistance intensified following the desecration of Moro tombs.[2] In search of gold and other treasures, Spanish marauders looted and burned the tombs of Moro sultans and missionaries—places that were considered to be sacred. Their ignorance and disregard of Muslim beliefs and practices generated tension and increased Moro distrust of Spanish rule, which continued for centuries.

When the Americans arrived in the Philippines in 1898, the Moro people had maintained their distance from their hispanized neighbors in the North. In many ways the history of Moro resistance shaped the approach of the US military towards colonization. Unlike the Spanish, the US military’s primary aim was to exterminate the opposition and to pacify the country in preparation for a different kind of colonial rule. They claimed that the Moros would maintain their practices and beliefs.

US Military Rule: Ending the Moro Resistance

In 1903, the US military established the Moro Province (which included the Muslim-dominated territories of Mindanao and Sulu) as a new legal division to be administered by a US Army commander separate from the Christian Philippines. According to the census taken that same year, the Moro Province had a population of 395,000 spread over 38,888 square miles.[3]

The response of the Moro people towards US military rule was mixed. Some groups allied with the US military while others resisted. This can be explained in part due to the fact that the Moros represent ethnolinguistically diverse groups of people. According to historian Patricio N. Abinales, the US military made alliances with “friendly datus,” or leaders of the “disunified” Muslim communities, and focused on building relationships with the locals that would destroy the opposition.[4] Abinales further explains that the divisions among Moros were actually beneficial for US military objectives. The pacification campaigns of the US military depended on a “combination of suppression and accommodation,” meaning that they not only used force to subdue the Moro population but they also sought collaborations.[5] The US military drew from their experience with Native Americans, in which they allowed Indian collaborators to keep arms and police their own people.

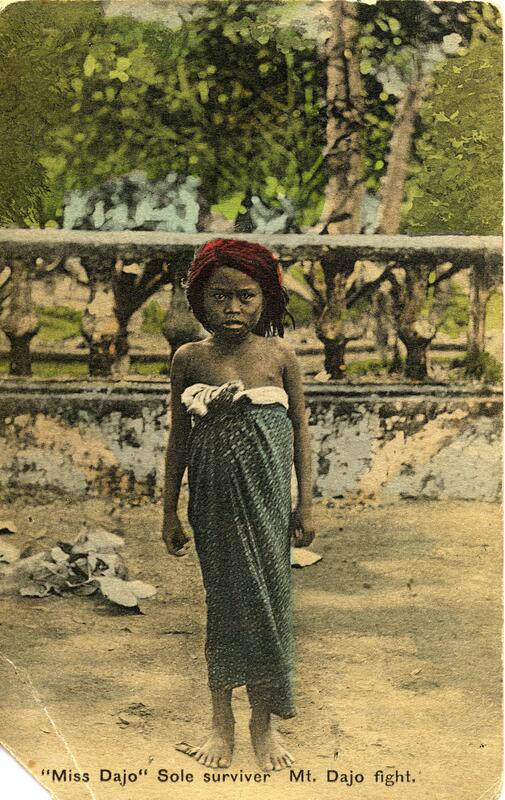

While some alliances with Moro leaders were successful, others were not. Well after the Philippine-American war was officially declared over in 1902, Moros continued to fight for their freedom. The US military referred to the uprisings that occurred throughout 1903-1913 as the “Moro rebellions,” and they also described these events as “armed conflicts.” This language strategically downplayed the violence and brutality of the US military in suppressing the opposition. These so-called conflicts were, in reality, massacres of Muslims who resisted US military rule, including civilians. One major event is known as the Bud Dajo massacre of 1906. Over 600 Moro men, women, and children were murdered within a crater of a dormant volcano in Jolo called Bud Dajo.[6] The majority of those killed in the massacre were women. US troops fought with rifles, machine guns, and explosives while the Moros were armed with blades such as the barong knife, a weapon that originates within Moro culture. Due to their disadvantage in arms, Moros tried to smuggle or steal firearms whenever they had the opportunity to do so.[7] Considering these inequalities, the Moro Rebellions can more accurately be described as a series of ruthless killings of anyone, even civilians, who resisted.

The US military’s pacification campaign, while relying on both suppression and accommodation, was eventually successful. In 1906, US officials noted that Lanao, an area of the Moro Province, had become pacified, and other areas of the region followed soon after.[8] Part of these successes in pacification had to do with the infrastructure that the US military created that allowed for Moro participation in internal trade, thereby promoting economic self-sufficiency in the province and discouraging anti-American warfare. Most datus (community leaders) no longer wished to fight.

The US military’s reframing of the massacres also supported their pacification efforts. They strategically constructed the Moro as an “ideal” colonized subject, a discourse that erased the violence of US troops in the Moro Province and rewrote their violent actions as heroic military service. In calling the massacres of Moro people “armed combat” during wartime, and promoting the idea of Moro “primitivity,” the US military changed the narrative of US brutality in support of the colonial project. They used gender to construct the Moro women as masculine and argue that all Moros were “fierce” warriors due to their primitive “nature.” Doing so helped to justify their actions.[9]

Using gender to reframe US violence against the Moros also worked to promote US imperialism. The image of the Moro as a “submissive but not conquered” subject—the perfect combination of accommodating but strong—served the US narrative of guiding the Moro people towards modernity.[10] Instead of “conquering” the Moro, the US was, according to this narrative, interested in developing the Moro’s potential within their already “superior” culture (superior at least in comparison to the emasculated, hispanized Filipinos of the North). Ultimately, the construction of the Moro subject was a means to elide US military violence against the Moro people, promoting collaboration and aiding in the long-term US imperial mission.

Representing the Moro: Michigan Men Colonize the Southern Philippines

“Michigan Men”—faculty and alumni from the University of Michigan known for their administrative roles in the US colonial Philippines—played an important role in producing the image of the colonized Moro subject. The representation of Moro people and culture within the archives of Michigan Men supported the US military’s narrative, which downplayed US violence and justified colonialism. These Michigan Men included Dean C. Worcester, Joseph Beal Steere, and Joseph Ralston Hayden. In this section, we will focus on the papers of Joseph Hayden.

Joseph Ralston Hayden was an alumnus and political science professor at the University of Michigan who became a “recognized authority on the Philippine Islands.” In his publications and presentations at the University of Michigan, Hayden characterized the Moros as a primitive people who were difficult to “civilize.” He stated,

The Moros had a strong tradition for being refractory to all reduction and civilization; it is the history of the entire Spanish regime. The most pertinacious and vigilant intention of really revolting, whether by strength or craftiness, was the attitude and constant disposition of the average Moro against the dominant nation.[11]

The perceived propensity of the Moro towards disobedience that Hayden described reflected the arguments of the US military. This perspective emphasized Moro masculinity to construct an image of a strong, defiant warrior in contrast to the effeminate, hispanized Filipino.

The image of the Moro as physical, and beast-like, served to counter the idea that the US military enacted barbaric violence against innocent women and children. According to Hayden,

[The Moro] has unlimited confidence in himself specifically his physical powers. He is industrious, taking rank in this regard above his more civilized Filipino brother… of all the Moros, the Joloanos (Sulus) are the most persistent in their determination to resist rational control by the government. These people, hitherto generally well-armed, have literally fought every forward step the authorities have attempted.[12]

Hayden made a direct comparison between the Moro and “his more civilized Filipino brother,” differentiating Muslims in the southern Philippines as incapable of civilization. Moreover, Hayden essentialized the Moro as “physical” rather than intellectual and claimed that they were unwilling to accept “rational” control. Such descriptions not only characterized the Moros as inferior subjects but also dehumanized them in a way that could absolve the war crimes of US troops. According to this logic, how could the US military commit “murder” against the non-innocent?

The discourse of the US military, which characterized Moros as ignorant, also focused on religious practice. US soldiers claimed that the Moros were not “truly” Muslim because they transgressed Quranic teachings. They constructed Moro immorality by pointing to their participation in “gambling, drinking, adultery, and especially the enslavement of other Muslims, all expressly forbidden by the Koran.”[13] George W. Robinson, a US Marine from Michigan wrote, “it would be worse than useless to try to sell any books of learning out here, these people would not know what a book was. If they saw it they would think it was something to eat.”[14] According to the US military’s depiction, Moros lacked the intellectual capacity for civilization.

This image of the Moro as physical rather than intellectual not only erased US violence, but it was also tied to furthering the colonial project. Michigan Men argued that the Moro’s physical power, a “savage” strength, came from the land they settled. US military officials such as Joseph Hayden argued for the US’s role in civilizing the Moro to use their land and physical “power” to advance US imperialism. Hayden’s emphasis on Moro agriculture and dwellings supported the idea that Moro territory represented economic and strategic value for the US. He wrote, “The Moros occupied the most advantageous positions in Mindanao; they controlled the streams and the bays.”[ 15] Ultimately, the discursive construction of the Moro as primitive served multiple aims of US imperialism, justifying violence, control, and also promoting an economic imperative.

Moro Resistance and US Military Violence Today

The history of US military colonialism and Moro resistance in the southern Philippines is important for multiple reasons. Firstly, it is an understudied history that has been overshadowed by the focus of historians on the Christian Philippines. It is also a history that has been silenced through institutional narratives within US colonial education. Most mainstream and public history books, websites, and media claim that the Philippine-American war officially ended in 1902. However, fighting and resistance continued in Mindanao by the Moro people the entire time that the US military occupied the region, from 1898-1913.

Secondly, we can learn from the history of Moro resistance by paying attention to the connections between past and present. The Moro resistance was the first encounter between the US army and a Muslim armed force. This experience has influenced the US military’s approach to Muslim “enemies” throughout the twentieth century, and into the present day.

Many of the same violent strategies that the US military deployed against the Moro people have been retooled in US wars in the Middle East, especially in Iraq and Afghanistan. The similarities between the US occupation of the Philippines and military interventions in the Middle East are striking. These connections are even made by US leaders. US President Donald Trump, for example, praised the military service of General John J. Pershing of the US Army in the Philippines for his mass killing of Moros, including civilians. He tweeted, “Study what general Pershing of the United States did to terrorists when caught there was no more Radical Islamic Terror for 35 years!”[ 16][ 17] Displaying hatred of Muslims and racist violence, Pershing dipped bullets of pig’s blood and used them to kill the Moro opposition. Trump’s suggestion that the US military deploy the methods of General Pershing to the Middle East reflects colonial violence today. This connects back to the history of Moro resistance and US military imperialism in the southern Philippines.

Citations

[1] Michael C. Hawkins, "Managing a Massacre: Savagery, Civility, and Gender in Moro Province in the Wake of Bud Dajo." Philippine Studies 59, no. 1 (2011), 102.

[2] Cesar Adib Majul, Muslims in the Philippines, Asian Center (1973), 94-95.

[3] Patricio N. Abinales, Making Mindanao: Cotabato and Davao in the Formation of the Philippine Nation-State (Ateneo University Press, 2000), 19.

[4] Ibid, 20.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Michael C. Hawkins, “Managing a Massacre."

[7] James R. Arnold, The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913 (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2011).

[8] Patricio N. Abinales, Making Mindanao, 20.

[9] Michael C. Hawkins, “Managing a Massacre," 90-93.

[10] Ibid, 89.

[11] Folder 12. Box 30, Joseph Ralston Hayden papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Michael C. Hawkins, Making Moros: Imperial Historicism and American Military Rule in the Philippines’ Muslim South (DeKalb, IL: NIU Press, 2013), 61.

[14] Letter from George W. Robinson to family (May 8, 1903). George W. Robinson papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[15] Hayden: Public Order Among the Moros and the Work of the United States Army, 13, Folder 12. Box 30, Joseph Ralston Hayden papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[16] Linda Qiu, "Study Pershing, Trump Said. But the Story Doesn’t Add Up." New York Times vol 17 (2017).

[17] Donald Trum, Twitter post. Aug 17, 2017, 11:45 AM.