Igorots in Detroit

Detroit and Electric Park

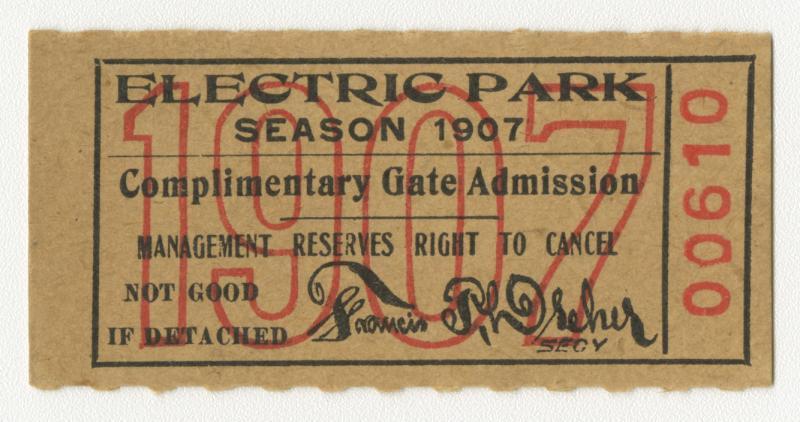

In 1907, crowds gathered at Electric Park in Detroit to visit the popularized touring Igorot Village as mentioned in Displaying the Filipino Primitive. To understand the context of the exhibition, it is helpful to know the history of Detroit and the park itself. Electric Park was built only a year before the Igorot Village arrived. The Isle was initially Indigenous land, and Electric Park’s first name was reflective of that named Anwebida which meant “Here let us rest” in Chippewa. [1] However, the park did not gain popularity and so it closed for three years, reopening under the new name, Electric Park. But it was a place of recreation reclaimed by white people. Admission to the park was only 10 cents. It was made intentionally affordable because “part of the entertainment was experiencing the ‘great mixed mass of humanity’.” [2] Even so, in images of Belle Isle, there are no minorities pictured partaking in these activities.

Detroit itself was fairly diverse at the time. In 1900, twelve percent of the city’s population did not speak English.[3] The influx of immigrants occurred between 1900-1919 and many were able to find jobs because of the fast-growing automobile industry in the city. In 1903, the Cadillac Automobile Co. produced its first car, and the same year saw the Ford Motor Company incorporated. Five years later in 1908, The General Motors Company was formed. [4] This period of time was one of great industrial growth bringing in many different companies and people. So, it does not feel surprising that the Igorot touring manager Richard Schneidwind decided to make a stop in this fast-growing city which also happened to be his hometown. There were many people and opportunities to make a profit. In addition, with Detroit’s racial makeup, the majority, if not all, of the visitors were white, and so they most likely saw little to no issue with the exploitation of the Igorot people. To them, it was just a part of their weekly recreational time at Electric Park. Having been born and raised in Detroit, this may have been more of a reason for Schneidwind to return and be welcomed to hold such an exhibit. In a way, the Detroit people were his people and he knew that this was something they would be receptive to.

The Igorot Village went to Detroit only three years after the first appearance at the St. Louis World Fair. It was also only one of many stops that came out of the World Fair, the history of which is better known.

St. Louis World Fair and the Filipino Exhibition Company

The St. Louis World Fair was seen as a magnificent exposition of the time. Held from April 30th to December 1st, 1904, the fair had many exhibitions. The director of exhibits “planned exhibits showing man and his works” as a way to display “education characterized by life and motion” which was the theme of the fair. [5] One of these exhibitions was the “Philippine Reservation.” It was the largest exhibit at the Fair which was separated by a body of water named Arrowhead Lake. [6] The reservation was 47 acres with 1200 Natives, 725 Native Soldiers, and 40 different tribes. It was described as “better than a trip through the Philippines Island” and a “movement to make a display that would give to the Western world a new impression of the Philippines.” [7] So the exhibit was to both gain public support for U.S. foreign policy and also to “familiarize Americans with their recent acquisitions.” [8] In 1904, it had only been two years after the Philippine-American War. They also argued that it was to introduce the people to American culture and civic values. [9] This furthers the belief of the “white man’s burden” the fair was trying to display. The ideas of U.S. imperialism and the belief in the white man’s burden are prevalent in the display and treatment of the Filipino people.

The Igorots were an indigenous group from Luzon. It is possible that out of all the indigenous groups, the Igorots were chosen to tour because of their practice of headhunting. Instead of understanding their cultural practices, it was used as a headline to draw in crowds. “Igorot” also means people from the mountain, so this could have been just used as a general term to group the people together without regard for the actual ethnic group they belonged to. This generalization and grouping can be seen as another consequence of U.S. imperialism. Schneidewind who served during the Spanish American War worked at the St. Louis World’s Fair where he first encountered the Igorot Village. In 1905, Schneidewind partnered with Edmund A. Felder—the Executive Officer of the Philippine Exposition Board at the St. Louis World's Fair—to form the Filipino Exhibition Company. [10] The Reservation and the tours gained praise from figures such as President Roosevelt. Schneidewind brought the Igorot Village across the country, Canada, and even Europe until 1912. His group ranged from 40 to 55 people with some going on multiple tours before returning back to the Philippines. Some of the Fairs they went to were West Michigan State Fair, Great Iowa State Fair, Louisville, Empress Rink Nottingham (Dec 18, 1912), Cedar Point Ohio, Minnesota State Fair, La Crosse Inner-state Fair (Sept 22-25, 1908), New York Fair (1907), Riverview Park Illinois, Kentucky, Comstock Park (Sept 14, 1908), Luna Park Pittsburgh, Seattle State Fair, The Palladium, Chutes Park Los Angeles (Dec 16, 1905), Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (1909), Electric Park Detroit (1907), Toronto (1906), Paris, England, and Belgium. [11]

It also should be noted that Schneidewind was not the only manager of a group of touring Igorots. Truman Hunt also got together his own group to exhibit at fairs. Hunt was actually the manager of the Igorot Village at the World Fair. The fact that there were multiple groups demonstrates how profitable this exploitation of humans was for almost a decade following the initial Reservation in St. Louis. While Schneidewind’s treatment of his group was better than Hunt in terms of salary payment and living conditions, [12] in 1911 when Schneidewind's company began experiencing financial issues, his goodwill seemingly came to an end as “newspapers reported about starving Igorots wandering the streets of Ghent, Belgium.” [13] The exploitative exhibiting of the Filipino people was finally put to an end by the U.S. government in 1914. Why these tours were able to go on for so long is unclear as it seems that the initial message the U.S. government wanted to display became lost over the years. It does seem that the intentions behind it were different when it came to other state fairs. In St. Louis, it fits their theme and the specific agenda that went with it–which was, of course, problematic–but it seems the other places, it was more about the profit that they felt they could make from the exhibiting of the Igorot Village.

A particular image of the Igorots was created since the St. Louis World Fair and it was continuously perpetuated throughout the tours. At the St. Louis World Fair, the Reservation had multiple Indigenous groups. In a pamphlet for the Reservation, many of the different tribes were highlighted. But the way they would be talked about felt very much like how different species of animals are described. The pamphlet talked about how they looked and their temperament. It pointed out which ones were the most peaceful group or the best looking.[14] Because the attitude towards them began this way and was successful, it is not surprising that the newspapers really played into how the touring village was a sort of human zoo. The Igorot people were described as head-hunting barbarians, wild, savage, a childhood of a race, and “more than two thousand years backward in the scale of civilization” [15] in multiple newspapers. Detroit was no different in how they viewed the Igorots as a group of savages. It seems that there was actually no exception to this view.

Media Representation and Coverage

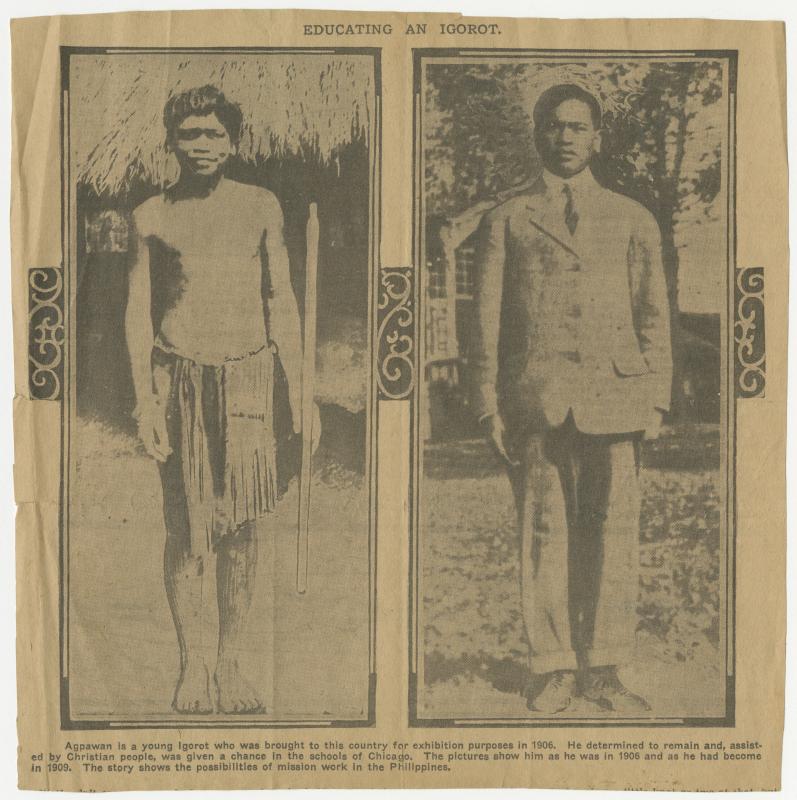

There were only a couple of times the papers focused specifically on the Igorot people as people rather than a spectacle. But even in these moments, the shred of humanity that the papers granted them was to further highlight the U.S. as better. For instance, one newspaper shared a photo of Agpawan a young Igorot man who arrived in the U.S. in 1906. Whether he was a part of the touring group that stopped at Detroit is unclear, but it is possible given the year. The caption reads, “He determined to remain and, assisted by Christian people, was given a chance in the schools of Chicago. The pictures show him as he was in 1906 and as he had become in 1909. The story shows the possibilities of mission work in the Philippines.” [16] It was rare for any of the Igorot people to be named. Often the only names that were written in the papers were the interpreters. Here, naming Agpawan humanizes him. But also giving him this space was a sort of success story for the U.S. It showed how the tours were helping to educate the Filipino people and helping them into civilization, or in other words, fitting into American society. It also subtly confirmed the belief that these tours were not harmful to the Igorot people. The photo of Agpawan in 1909 is him dressed in a full suit. The fact that that was the image they chose plays into the idea of savagery connected to clothing. In multiple papers, the Igorot people’s lack of clothing was mentioned. In Nashville, the deputy sheriff arrested some of the people in the village for indecent exposure. It mentions that this was partly because the deputy sheriff had no idea about the custom of the village. If the tours’ intent was partly to educate the American people about the customs of the Igorots, this could be seen as a failure on the part of the tours. In other ways, this was a way of further dehumanizing the Igorot people and setting them apart from what was considered the law and order of civilized society.

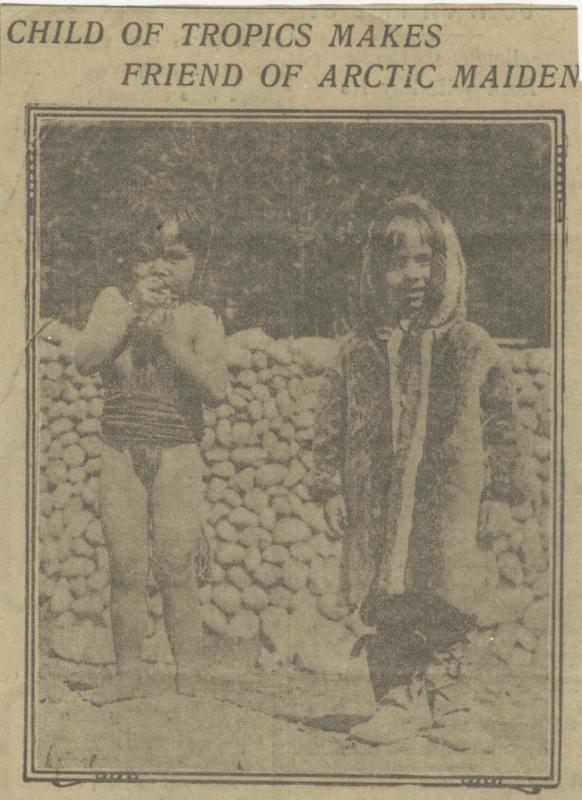

Other instances where the newspapers focused on the people occurred when they talked about the children in the villages. One paper describes them as “a great deal like other youngsters, of other colors than brown, and they are given to a belief that lifetime is playtime. . . kids are kids, even in Bontoc, and also in the Igorot Village at Seattle’s big fair.” [17] Another paper, talks about Peu-Yok a young Eskimo girl playing with Wai-Ye at the Igorot village. The paper describes the way they play and talk with each other even though they do not share a language. [18] In both cases, the children’s names are shared, and there is a level of understanding and empathy that can emerge seeing how children are always children. But again, this still plays into the perception that the Igorot people as a whole were lesser than, and childlike compared to the more civilized whites.

The lack of names contributes to the erasure of their identity and further the erasure of these tours as a whole. It becomes more difficult to follow the people and understand what their experiences were on these tours. Currently, reparative work is being done, both to bring forth this history and also to identify and honor those involved. Artist Janna Langholz is currently working to help name those who were in the St. Louis World Fair while also honoring those who had passed on the Reservation by giving them proper headstones. [19] Because those who were a part of the traveling tours changed, it is extremely difficult to name and identify all those who were part of the Igorot Village, but beginning where we can, in St. Louis, is an important first step at addressing this history. Especially because the tours went on for almost a decade, and should be given attention as part of the long list of unsettling, inhumane events that occurred in U.S. history.

Citations

[1] Clarence J. Monette, Houghton County's Streetcars and Electric Park (Lake Linden, MI, 2001), 110.

[2] Cheri Y. Gay, Lost Detroit (London: Pavilion, 2013), 49.

[3] Frank B. Woodford and Arthur M. Woodford, All Our Yesterdays: A Brief History of Detroit (Detroit, Wayne State University Press, 1969), 245.

[4] Woodford and Woodford, All Our Yesterdays: A Brief History of Detroit, 370.

[5] Astrid Böger. Envisioning the Nation: The Early American World's Fairs and the Formation of Culture (Frankfurt: Campus, 2010), 187.

[6] Böger. Envisioning the Nation: The Early American World's Fairs and the Formation of Culture, 197.

[7] Alfred C. Newell, "Philippine Exposition." Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[8] Böger. Envisioning the Nation: The Early American World's Fairs and the Formation of Culture, 197.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Richard Shneidewind papers 1899-1914, Finding Aid, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[11] Richard Shneidewind papers 1899-1914, Admission Tickets 1905-1909, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[12] Claire Prentice, The Lost Tribe of Coney Island: Headhunters, Luna Park, and the Man Who Pulled off the Spectacle of the Century (Boston, MA: New Harvest 2014), 190.

[13] Richard Shneidewind papers 1899-1914, Finding Aid, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[14] Alfred C. Newell, “Philippine Exposition.” Clements Library, University of Michigan.

[15] Richard Shneidewind papers 1899-1914, Newspaper Articles 1905-1913, Box 1, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Jannna Langholz, “1,200 Lives and Deaths at the World's Fair,” October 22, 2022 https://www.jannalangholz.com/1200-lives-and-deaths.